Jungian Psychology, Minus the Nonsense

Making sense of an esoteric theory of mind

View on SubstackMinus the Nonsense is a series on valuable ideas that have been tainted by magical thinking. We’ll try to distill the good parts—the parts compatible with a scientific worldview—from the woo. Future subjects will include Taoism, Karma, and Enlightenment.

Carl Jung is a controversial figure in the history of psychology. His best ideas—including concepts like introversion, the persona, and personality types—have been absorbed by the mainstream. But some of his ideas are explicitly mystical and lack scientific rigor.

The body of Jung’s work is too broad for a single article. So for now, let’s focus on his map of the psyche.

Outline

Note: this article represents my own digestion and synthesis of Jungian ideas. I draw from Jung himself, Marie-Louise von Franz, James Hillman, Robert Moore, and others. Not every Jungian—nor Jung himself—would agree with everything here.

Growing the Psyche

We tend to think of children as “blank slates”—they begin empty, and build up a personality over time. Through imitation, they accumulate knowledge, behaviors, and habits.

The Jungian view turns this on its head. It sees the newborn as an undifferentiated whole—more like a slab of marble than an empty canvas. It’s the job of the parents and community to pare away parts of the psyche that are antisocial or taboo.

From the Jungian perspective, the infant has latent potential for all kinds of love, violence, hatred, passion, and desire. Anyone who’s spent time with a toddler knows they can transform from angel to psychopath and back again in a matter of minutes. Normal psychological development cuts away the antisocial behaviors, so our psychopathic toddler can become a functioning adult.

Jung’s great insight (building on Freud) is that these pared-away pieces of self don’t just disappear. Instead, they’re repressed, and remain dormant in the unconscious mind.

But the word “dormant” isn’t quite accurate—these fragments of personality temporarily reactivate in the controlled environment of dreams, and can resurface in response to change or stress.

An example:

A young boy has an innate sense that he can use violence to get what he wants. His parents quickly suppress this instinct through punishment, and he learns to play well with others. But he still enjoys stories with violence, and occasionally has dreams where he commits acts of brutality. As a young adult, he’s drafted into war; during boot camp this latent propensity for violence is dredged up to the surface, and he transforms into a warrior.

For Jung, personality is always in flux. We shuffle pieces of ourself above and below the surface in order to adapt to our society and to the situation at hand. The goal of psychoanalysis is to help us when we get stuck, or when find ourselves in an inappropriate configuration.

Partitioning the Psyche

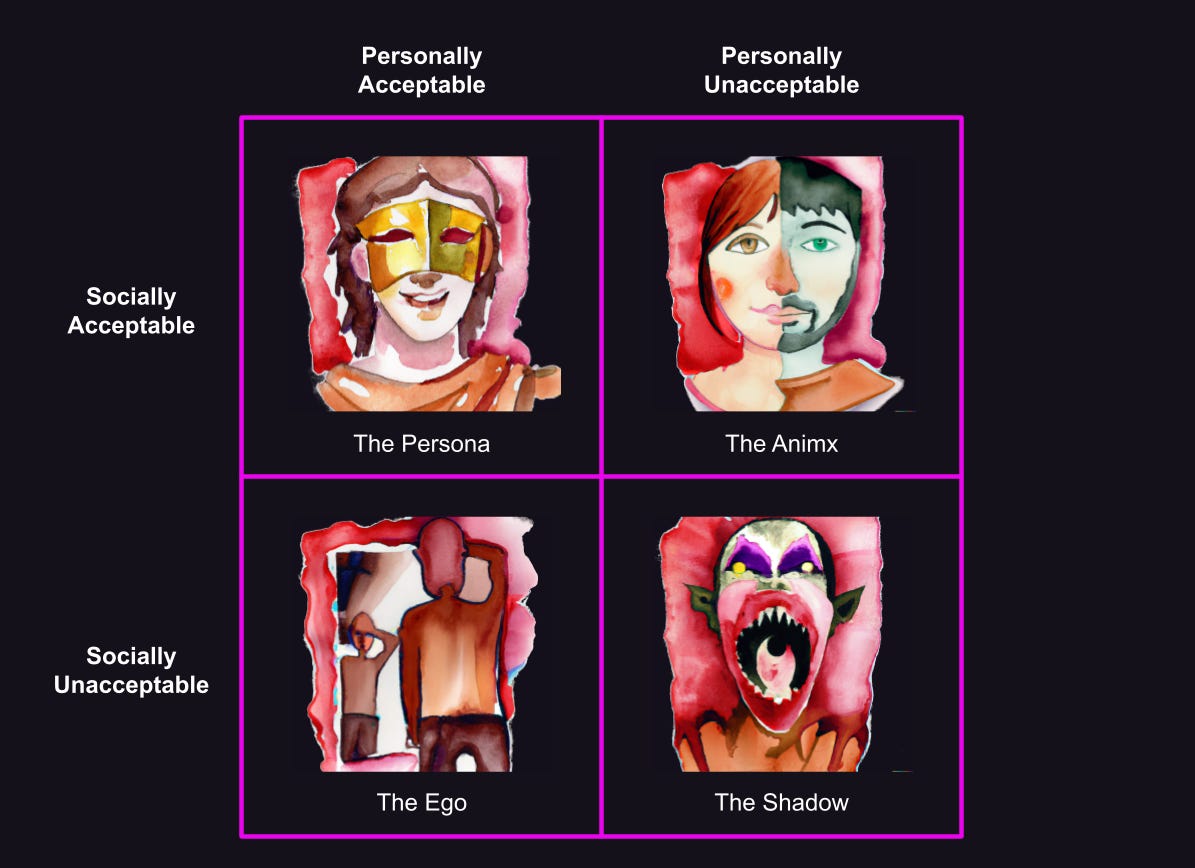

According to Jung, the maturation process leaves the psyche cut up into four distinct pieces. The first cut divides traits you accept in yourself, versus traits you repress:

Ego is the image you have of yourself

Shadow sits opposite the Ego, and contains all the traits you repress

Both are then subdivided with a further slice, based on what’s socially acceptable:

Persona is the subset of the Ego you present to other people

Animx is the subset of the Shadow that you find acceptable in other people, despite being personally unacceptable—typically traits associated with the opposite gender

We can put these pieces into a two-by-two matrix, based on what you find personally and socially acceptable:

To illustrate the differences, here are some examples:

Persona—I enjoy joking around with my coworkers between meetings

This is out in the open.

Ego—I’m attracted to one of my employees

I’m fully aware of this, but know better than to tell anyone.

Animx—I’m insecure about how my coworkers perceive my intelligence

I’d accept someone else’s insecurity, but don’t acknowledge my own. My insecurity may come out in weird and problematic ways.

Shadow—I want to hurt my rival coworker

I think of myself as a nice person, and am unaware of ways that I’m sabotaging or undermining my colleague.

The two-by-two matrix doesn’t give a perfectly clear picture of the situation though. In truth, the Persona and Animx are more like the surface-layers of the Ego and Shadow. And it helps to situate the whole thing relative to external reality and the inner world of dreaming and imagination.

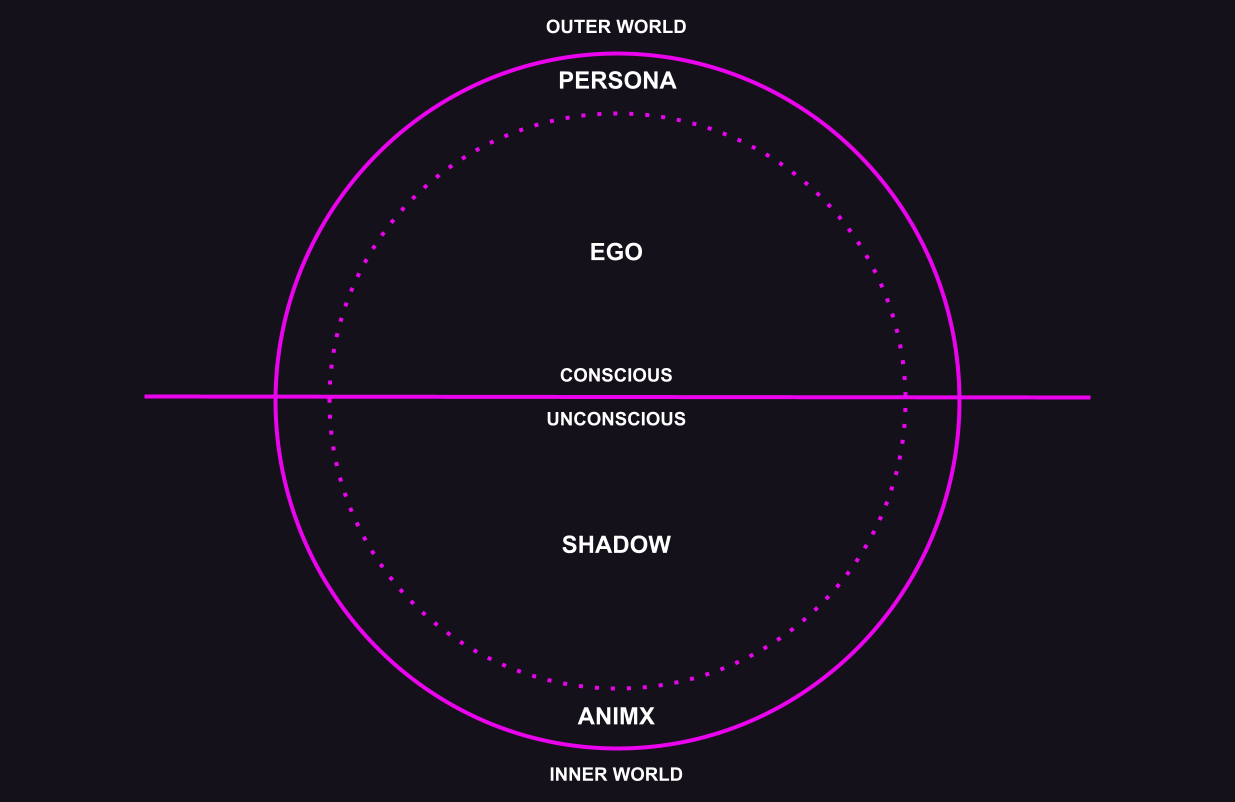

This diagram will be more familiar to Jungians:

Here, the strong circle is the Self, the whole undifferentiated person. The personally acceptable parts lie above the line of consciousness, while the personally unacceptable parts lie below. The socially acceptable parts of the personality appear at its border, while the socially unacceptable parts sit deeper.

So we’ve partitioned a person’s personality into four boxes. We shouldn’t see these four boxes as having sharp borders, or as being rooted in neurology. They’re simply a model for working with our emotions and behaviors, especially uncomfortable ones.

While you might find this model helpful or unhelpful, I hope it at least seems reasonable.

Most of us understand what we mean by Ego and Persona, since these concepts have been absorbed by mainstream psychology. So let’s dig a bit deeper at their unconscious complements: the Shadow and the Animx.

The Shadow

Unfortunately there can be no doubt that man is, on the whole, less good than he imagines himself or wants to be. Everyone carries a shadow

—C.G. Jung, Psychology and Religion

The Shadow carries traits that are universally reviled by your in-group—traits that you not only repress in yourself, but which you despise in others.

These traits are often projected onto an outgroup or a perceived enemy. The easiest way to see someone’s Shadow is to ask them who they hate.

The Shadow’s attributes vary from person to person and from culture to culture, but it’s often violent and cynical. A warrior’s shadow is a coward; a socialist’s shadow is greedy; an intellectual’s shadow is irrational.

Again, Shadow traits don’t disappear—they only sit below the surface. Every warrior has an inner coward; every socialist has the capacity for greed. Shadow traits mostly remain invisible—both to you and to the people around you—but, as we’ll see below, they can still emerge in dangerous ways.

For a deeper discussion of the Shadow, see my review of Facing the Dragon.

The Animx

You seek the feminine in women and the masculine in men. And thus there are always only men and women. But where are people?

You, man, should not seek the feminine in women, but seek and recognize it in yourself, as you possess it from the beginning. It pleases you to play at manliness, however, because it travels on a well-worn track.

—C.G. Jung, The Red Book

One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.

—Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

Not all our repressed traits are relegated to the Shadow. We understand that the world is full of different kinds of people, and that not everyone in the in-group should be identical.

Most prominently, this understanding takes place along lines of gender. We acknowledge that half of our in-group has traits that are generally desirable, but not appropriate for us personally. Jung named these traits Anima (for men) or Animus (for women). For simplicity, I refer to both as the Animx.

Every time a man pinches himself to keep from crying at a sad movie, or a woman backs down from an argument for fear of seeming combative, they’re pushing some of their traits out of their Persona and back into the Animx.

Jungians will often talk about the Animx explicitly in terms of gender, but this is an oversimplification. A more principled way to think about the Animx is as a counterpart to the Persona. It embodies all the traits we find in the faces of our friends, but don’t identify with personally.

So the Animx varies even more heavily from person to person than the Shadow—the shadow is a reflection of the out-group, while the Animx is a reflection of the in-group.

Possession

Traits relegated to the Shadow and Animx have a tendency to surface spontaneously. Jung, with mystical flair, refers to this as “possession” (we’ll discuss the implications of this word in the Nonsense section).

We always find indirect ways to express our unconscious traits—hopefully healthy ones. You might think of yourself as peaceful and non-violent, yet love war movies and BDSM. For Jung, this isn’t a contradiction; it’s a healthy engagement with the Shadow.

But if a trait is repressed too heavily, it can emerge in unexpected and problematic ways: a cruel joke, an outburst of anger, an infidelity. Maybe a stoic man has a nervous breakdown, or a meek housewife has a steamy affair1. We browbeat some unseemly part of ourselves into submission, until it finally reaches a breaking point and bursts out.

It’s hard for me to justify the concept of Possession on logical or scientific grounds—it’s not the sort of thing that lends itself to laboratory study or surveys. But every time I catch myself acting “out of character”—especially doing or saying something I know is hurtful—I come back to this idea.

An example: at a recent party, I was goaded into putting on a pair of high-heels and strutting down a makeshift runway. Words cannot describe how out-of-character this was, or how gratifying it felt. I like to think my Anima got a moment to surface and breathe.

Projection

Projection is an important concept for Jung. Our self-image is always complemented by our image of other people. The traits we repress internally appear everywhere externally.

This is almost true by definition. You can’t think of yourself as smart/brave/interesting unless you think other people are dumb/cowardly/boring by comparison.

What’s more, you’re primed to see these anti-traits even when they’re only weakly present—our brains are wired to spot differences, while sameness fades into the background. So the ways in which people are different from us (or more specifically, different from our self-image) stand out.

This works a bit differently for the Animx and the Shadow, so let’s dig into both separately.

Shadow Projection

The easiest way for us to ignore our own worst qualities is to see them in other people. If I focus on your greed, mine fades in comparison. If I focus on your weakness, I feel strong. We do this constantly.

The Shadow most easily comes to the fore when the in-group gathers together. They collectively project their Shadow—all the traits they revile—onto the out-group, which is condemned as evil, insane, or less than human.

Worse, by denying the out-group’s humanity and casting them as a threat, the Shadow gains an excuse to emerge. It can act out its violence and rage with full justification. Projection enables Possession.

The canonical example here is the Nazi Party, which (among other things) believed Jews were murdering children, an ended up murdering over a million Jewish children. But the whole point of Shadow work is to recognize your own dark side, so I like to point to Americans post-9/11: we called for the heads of “freedom-hating” terrorists while tossing our civil liberties out the window; and we conducted a War on Terror that was nothing short of terrifying.

It is a frightening thought that man also has a shadow side to him, consisting not just of little weaknesses and foibles, but of a positively demonic dynamism…let these harmless creatures form a mass, and there emerges a raging monster; and each individual is only one tiny cell in the monster’s body, so that for better or worse he must accompany it on its bloody rampages and even assist it to the utmost.

—C.G. Jung, On the Psychology of the Unconscious

Animx Projection

Unlike the Shadow, The Anima contains traits that we see as acceptable or even desirable. As a result, people often project their Animx onto romantic partners2. We seek out the part of ourself we’ve repressed, and try to connect with it externally.

Too many guys think I'm a concept, or I complete them, or I'm gonna make them alive. But I'm just a fucked up girl who's looking for my own peace of mind. Don't assign me yours.

—Clementine in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

(And written by Charlie Kaufman, who is pretty into Jung)

Think of the average male looking for his manic pixy dream girl. His own sense of whimsy and spontaneity is hidden behind an Ego modeled after James Bond. So he looks for a partner who can safely act out those emotions for him.

This is mostly healthy and normal. If my Persona neatly complements your Animx and vice versa, we’ll get along great. I might even say something hokey like “you complete me”, and in a fairly literal sense it’d be true.

But in the long term, Animx projection causes pain and disappointment. You carry a two-dimensional image in your head of your ideal partner; when your actual three-dimensional partner drops their Persona and fails to live up to that ideal, you feel let down, even betrayed.

And Animx projection isn’t always gendered and romantic. Maybe you see your parents as morally upstanding, or a same-sex friend as highly intelligent. When they inevitably do something wrong or stupid, it’s disorienting.

Part of Jungian analysis is learning to recognize when you’re projecting your ideals onto other people, instead of seeing the whole person.

Integration

So unconscious traits are dangerous—they distort our self-image and our image of others. And they can surface in problematic ways.

To alleviate the danger, Jungians try to cast light on the unconscious. We’re encouraged to look at ourselves with a sober, dispassionate eye, and accept what we find, no matter how shameful or frightening.

The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside as fate. That is to say, when the individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner opposite, the world must perforce act out the conflict.

—Carl Jung, Aion

Jung called this process “integration” or “individuation”. As individuation progresses, the result is a deeper, more dynamic personality. You’re able to draw from a well of different personality traits, instead of relying on the habitual character you were raised to play.

Take, for example, someone who’s grown up to be meek and conflict-avoidant. This trait might serve them well enough, until someone takes advantage of them. But if they’ve properly integrated their Shadow, they can tap into a more violent, conflict-hungry self, which will happily stick up for them. (Scott Alexander has some related observations here involving Dissociative Identity Disorder.)

Bringing these traits into the light—seeing and accepting even your worst qualities—can not only save us from the twin dangers of Possession and Projection; it can give us a sense of wholeness, a deep sense of well-being.

But it’s profoundly difficult work, even painful. And it’s a never-ending process.

The shadow is a moral problem that challenges the whole ego-personality, for no one can become conscious of the shadow without considerable moral effort. To become conscious of it involves recognizing the dark aspects of the personality as present and real. This act is the essential condition for any kind of self-knowledge.

—C.G. Jung, Aion

The Nonsense

To recap: we’ve divided the personality into conscious and unconscious traits, shown that the unconscious ones wreak havoc, and therefore advocated for making them more conscious.

Again, while you might find this model helpful or unhelpful, I hope it at least seems reasonable. At a high level, Jung is simply saying “know thyself” while pointing out how radically hard that is.

With all that established—where does the nonsense come in?

Dream Interpretation

Jung’s critics often poke at his obsession with dream interpretation. Jung saw his unconscious characters—the Shadow and the Animx—in every patient’s dreams, and took this as irrefutable evidence of their realness.

But often Jung seems to project his ideas onto his patients’ dreams. Every woman that appears in a man’s dream, he labels “Anima”; every monster or villain is “Shadow”. Other characters were worked into a broader set of recurring archetypes.

While I’ve argued in the past that dreamwork can be a powerful psychological tool, using the content of dreams as evidence for anything is fraught with danger. Dreams are inherently fuzzy and easily influenced.

The Archetypes

To make things even fuzzier and unscientific, Jung’s archetypes bleed into one another. There are no firm, testable boundaries. Any dream character can be assimilated into Jung’s system of archetypes.

Personally, I find the Anima, Shadow, and other archetypes to be helpful concepts when examining my own mind (you might even recognize them in the dream I reported here). But that doesn’t mean I believe they exist intrinsically. They simply give me a helpful vocabulary.

An analogy might help here: there’s no principled reason for dividing the color spectrum into red-orange-yellow-green-blue-indigo-violet. But these artificial divisions are still useful for describing color. The same could be said of the Archetypes, even if some Jungians reify them beyond justification.

Autonomy

Jung often talks about the Shadow and Animx as autonomous, independent beings. They have their own wants, needs, fears, and hopes. And they’re capable of “possessing” the individual.

I see that many of my pupils indulge in a superstitious belief in our so-called “free will” and pay little attention to the fact that the archetypes are, as a rule, autonomous entities

—C.G. Jung, Letters Vol. II

This is obviously a bold claim, and (assuming the mind-body problem is as hard as it seems) an unfalsifiable one.

But seeing the Shadow and Animx as autonomous, even if we only take it as an as-if, can be very helpful. Here’s Marie Louise Von-Franz talking about the Shadow:

The shadow is not necessarily always an opponent. In fact, he is exactly like any human being with whom one has to get along, sometimes by giving in, sometimes by resisting, sometimes by giving love—whatever the situation requires. The shadow becomes hostile only when he is ignored or misunderstood.

This is, in my experience, true. It might only be myself that I’m resisting, loving, or ignoring, but externalizing the Shadow makes it easier to gain perspective (not to mention self-empathy).

And as long-time readers might be aware, I’m pretty open to the idea that I’m not the only person in my head.

The Collective Unconscious

Jung’s most controversial ideas revolve around his notion of the collective unconscious. This is more of an interpersonal, sociological phenomenon rather than a psychological one, so it’s outside the scope of this article. But it’s where his most outrageous claims originate, so let’s take a peek.

For one, Jung claims that there are universal symbols built into every human. These include the ouroboros, the wise old man, the tree of life, and the mandala. Jung often emphasizes that these symbols appear in the dreams of patients who had never previously seen them, but it’s unclear how he can be so confident.

Worse, Jung used his concept of the collective unconscious to advocate for perennial scientific bugbears like E.S.P., precognitive dreams, and astrology.

Despite all this, I think there’s some merit in the idea of a collective unconscious, which I hope to explore in a future Minus the Nonsense article.

Rejection of Science

But worst of all, Jung explicitly rejected psychological science, and refused to hold himself to its standards. He saw his theories as beyond science.

Anyone who wants to know the human psyche will learn next to nothing from experimental psychology. He would be better advised to abandon exact science, put away his scholar's gown, bid farewell to his study, and wander with human heart through the world. There in the horrors of prisons, lunatic asylums and hospitals, in drab suburban pubs, in brothels and gambling-halls, in the salons of the elegant, the Stock Exchanges, socialist meetings, churches, revivalist gatherings and ecstatic sects, through love and hate, through the experience of passion in every form in his own body, he would reap richer stores of knowledge than text-books a foot thick could give him, and he will know how to doctor the sick with a real knowledge of the human soul.

—C.G. Jung, Two essays on analytical psychology

This disdain for science allowed him to explore wild, grandiose claims about the nature of psyche, humanity, and reality. Had Jung been primarily a philosopher or a mystic, these sins might have been forgiven. But these ideas are dangerous for an academic psychologist, let alone a practicing clinician.

Models and Reality

Jung’s model of the psyche is a powerful one. His emphasis on bringing unconscious traits into the light of day is particularly important. Many of his best ideas have already been absorbed into mainstream psychology, and there’s at least some evidence that Jungian therapy is clinically effective.

But Jung took his own ideas too literally. He reifies the concepts in his model, asserting they have some intrinsic substance, even while admitting to the fuzziness of their borders and the unscientific nature of his claims. It’s important to remember that a model is only ever a model—we can’t mistake it for reality, no matter how useful it might be.

This literal interpretation has accumulated hordes of True Believers, who cling to his worst ideas while rejecting mainstream psychology as biased and limited. So it’s unsurprising that most serious psychologists avoid Jung’s work.

But I’ve personally found Jung’s model of the psyche to be profoundly rewarding, even if I have to sort through heaps of nonsense to find the fruit. It’s helped me grow as a person, and made me more comfortable in my own skin.

I’d encourage anyone with an interest in psychology or self-development to study Jung. Just don’t take him too seriously.

These examples are deliberately gender-normative. Gender roles are one of the strongest mechanisms for repression.

For simplicity, I focus on cis-hetero relationships here. But looking at trans and gay identities through a Jungian lens can be very rewarding.

It’s worth noting that Jung, like most of his contemporaries, pathologized queerness—though he was more accepting than most.

Join the discussion on Substack!