Split Brain Psychology

The strange interactions of Selfhood and Multiplicity

View on SubstackThere’s a thought which has consumed me—and at points, terrified me—for the past few years. What if I’m not the only person in my head?

Consider the possibility that at this moment, there are not one, but two conscious agents living inside your skull. There’s you, of course—but there’s also someone else, quietly living alongside you, viewing the world through your eyes, hearing what you hear, but with an entirely separate set of feelings, values, and desires. And imagine this alter ego isn’t simply an idle passenger. It (he? she?) has just as much control over your actions as you do.

It’s more likely than you might think.

Outline

Split Brain Experiments

What truly terrifies me about this thought experiment is that it has been carried out as an actual, real-world experiment. We’ve literally cut people’s brains in half. The results were weird.

(Note: there is some recent controversy surrounding these experiments. See [1] for analysis)

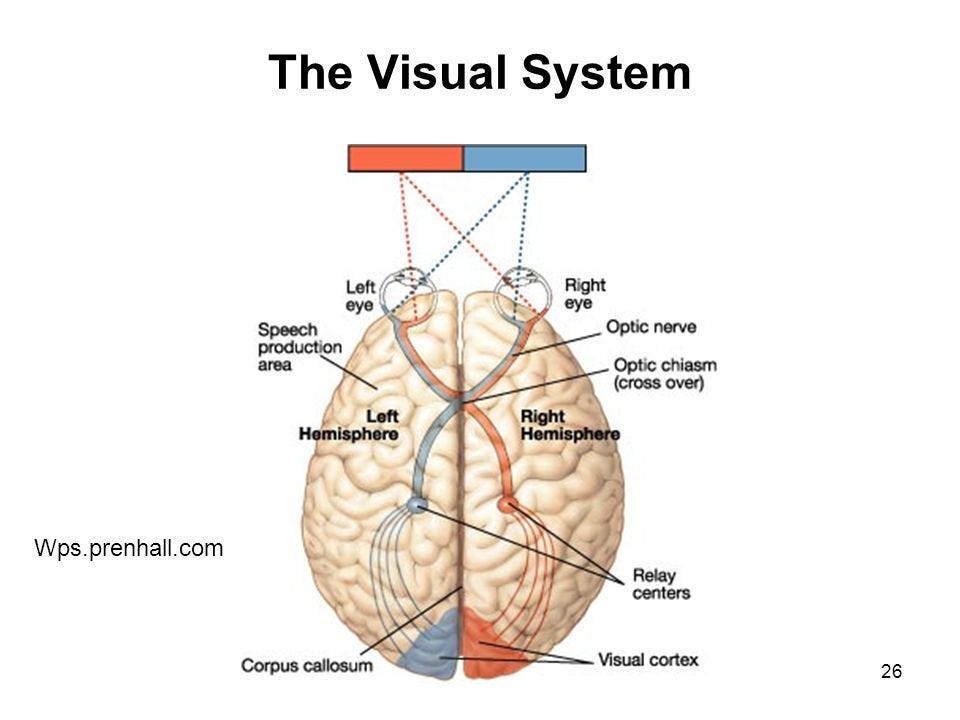

Our brains consist of two hemispheres, left and right, connected by a bundle of fibers known as the corpus callosum. Each hemisphere is connected to the opposite half of the body: the left hemisphere controls the right arm and leg, sees through the right eye, hears through the right ear; vice versa for the right hemisphere.

For a brief, strange period in medical history, patients experiencing seizures had their corpus callosum cut, physically separating the right and left hemispheres of the brain.

Post-surgery, there was often a period of conflict between the hemispheres:

When one split-brain patient dressed himself, he sometimes pulled his pants up with one hand (that side of his brain wanted to get dressed) and down with the other (this side did not). He also reported to have grabbed his wife with his left hand and shaken her violently, at which point his right hand came to her aid and grabbed the aggressive left hand.

- From Wikipedia

But it gets weirder! The two halves seem to quickly reach a working arrangement—within weeks to months, a split-brain patient can be difficult to distinguish from a neurotypical person. Importantly, the split-brain patient even regains their sense of unity, of being a single cohesive personality, despite their obviously fractured mind.

Which brings us to Michael Gazzaniga, a cognitive neuroscientist at UC Santa Barbara, and, according to Nature, the godfather of modern split-brain science.

Experiments

Gazzaniga has studied this residual sense of unity in split-brain patients. He attributes it to what he calls “Interpreter Theory.” Gazzaniga would present a task to the split-brain patient’s right hemisphere, then ask them to verbally explain their actions - a task typically only performed by the left hemisphere. Gazzaniga found that generally “the left hemisphere made up a post hoc answer that fit the situation.”

In one experiment, a patient’s left hemisphere was shown (via his right eye) a picture of a chicken foot, and his right hemisphere was shown a snowy scene. When asked to point out related images, his left hemisphere pointed (with his right hand) to a chicken head, while the right hemisphere pointed to a snow shovel—no surprise there. But something interesting happened when the researchers asked why he had pointed to the shovel:

[He] didn’t skip a beat: “Oh, that’s simple,” the patient told them. “The chicken claw goes with the chicken, and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.”

- The Atlantic, “One Head, Two Brains”

In other words, the left hemisphere, unaware that the right hemisphere had seen snow, constructed its own explanation as to why it had chosen the shovel. The left brain, despite being divorced from half of the body, still believed itself to be fully in charge.

Gazzaniga argues the same effect takes place in neurotypical folks, whose brains are perfectly in tact:

Our uniquely human skills may well be produced by minute, circumscribed neuronal networks, sometimes referred to as “modules,” but our highly modularized brain generates a feeling in all of us that we are integrated and unified. If we are merely a collection of specialized modules, how does that powerful, almost self-evident feeling come about?

…Because we have so many specialized systems, and because they may sometimes operate in ways that are difficult to assign to a given system or group of them, it may seem as though our brains have a single, general computing device. But they do not. Step one is to recognize that we are a collection of adaptive brain systems[.]

- Michael Gazzaniga, “The Interpreter Within: The Glue of Conscious Experience”

(Side note: this is very similar to the Thousand Brains Theory, which appears to be at least moderately useful for AI.)

According to Gazzaniga, even neurotypical folks are deluded into thinking of themselves as a cohesive whole. He claims that despite our stubbornly persistent sense of being a single person, we comprise an entire community of independent selves.

Multiplicity in Practice

So back to our thought experiment–if someone who literally has two brains can’t tell, how would you know if you had a few skullmates?

Let’s start from the conclusion and work backwards—does a multiplicitous model of the mind have any explanatory power?

I’d reply with a cautious “yes”: the language of multiplicity has inspired psychologists, poets, and mystics.

Psychology

Properly speaking, a man has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him and carry an image of him in their head.

- William James

Models of human psychology often decompose the mind into independent, autonomous agents. This divide-and-conquer strategy is most evident in the theories of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. They were the first to put forward the idea of an “unconscious,” of mental processes that happen outside our awareness.

Freud believed that our surface-level Ego was beset above and below by unconscious (or mostly unconscious) agents, the Id and Superego. The Id personifies our base instincts and animal drives—it seeks pleasure without regard for morality or consequence. The Superego, on the other hand, internalizes parental and societal values, and serves as a guide. With the Ego mediating between them, Freud’s mind is a perpetual negotiation between three independent and autonomous selves.

Jung expanded on this idea, identifying several other characters in the internal drama. Two important ones are the Shadow, an analogue of Freud’s Id, and the Anima/Animus, which carries the attributes of the opposite sex. Jung believed that we are born “whole”, experiencing the world in what Freud termed the oceanic state, but became fragmented as we were indoctrinated into a society that (rightfully) discouraged some of our behaviors while encouraging others. Any violent or anti-social instincts would be relegated to the Shadow, while gender-inappropriate impulses (according to that particular culture) would be placed in the Anima/Animus. These characters would remain dormant in healthy individuals, but would appear in dreams and fantasies. They could even “possess” the individual, causing them to engage in destructive or anti-social behaviors.

While the specifics of these theories no longer hold much water with contemporary psychologists, at the time they were revolutionary, and we can still see their legacy in theories like Internal Family Systems.

Mental Illness

The vocabulary of multiplicity is most obvious in discussions of mental illness. In particular, people suffering from Schizophrenia and Dissociative Identity Disorder often refer to other beings that live inside their brain.

Schizophrenic patients often hear disembodied voices. The voices can be pleasant and helpful, or (as in the Hollywood stereotype) derogatory and combative. There may be only a few voices, or there may be a cacophony. The voices appear to the schizophrenic as independent and autonomous.

(Please note that Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) and schizophrenia are very separate illneses. I don't have the space to discuss DID here, but I hope to talk more about DID in a future article.)

It would be easy to think of these voices as simple auditory hallucinations, rather than as auditory manifestations of hidden selves. But the voices seem to have the complexity and dynamism of individuals. They differ from culture to culture, and they respond to negotiation. It’s reasonable to hypothesize that there are actual selves behind the voices, somehow embodied in the schizophrenic’s brain.

Anthropology

One of the most controversial works of contemporary anthropology is Julian Jaynes’ The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. In it, Jaynes argues that early man was much like the split-brain patient: two independent hemispheres, each with its own specialization. Jaynes argued that the right hemisphere would induce auditory hallucinations in the left hemisphere, compelling it to act.

Richard Dawkins reviewed Jaynes’ book, saying, “It is one of those books that is either complete rubbish or a work of consummate genius; Nothing in between!” Despite the uncertainty and controversy, Jaynes’ work inspired some of the greatest thinkers on cognition, including Andy Clark and Daniel Dennett. At the very least, Jaynes’ idea that we are (or were) anything but unitary selves has sparked decades-long discussions on the nature of humanity.

If Jaynes isn’t your thing, Tanya Luhrmann is a (much more sober) psychological anthropologist who has spent much of her career investigating hallucinatory (she would say “imaginal”) beings, and their impact on the lives of the people who experience them. More on her below.

Mysticism

Man has no individual I. But there are, instead, hundreds and thousands of separate small "I"s, very often entirely unknown to one another, never coming into contact, or, on the contrary, hostile to each other, mutually exclusive and incompatible

- G.I. Gurdjieff

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

- Walt Whitman

In many traditions of mysticism and self-actualization, the key to transcendence is the unification of opposed forces. Even Jung’s teachings (which after his break with Freud, began to bleed into a syncretic mysticism) speak of “Individuation” and “Integration” of the many sub-selves into a cohesive whole. This, according to Jung, was the path out of neuroticism and into a happy, fulfilled existence.

We see the same ideas arise in the theories of Jung’s contemporary, the controversial G.I. Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff insisted that the individual is composed of “many 'I’s”, and broke these down into Intellectual, Emotional, and Moving centers. Studying these centers was a crucial part of the ardent self-examination that Gurdjieff’s students underwent in their quest for self-actualization.

In more traditional mystical practices, like those of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism, the aim is a bit stranger, but no different in character - to merge one’s individual, egoic consciousness with an undifferentiated ocean of Being. Here we have the same concept playing out in the macrocosm: a grand unified Self which is composed of billions of smaller selves.

But now a great thing in the street

Seems any human nod,

Where shift in strange democracy

The million masks of God.— G.K. Chesterton, Gold Leaves

The Turing Test

OK, so the concept of multiplicity has some explanatory power. But is it true? Are there experiments which could differentiate a solitary self from a multiplicity of selves?

Unfortunately, as any Solipsist will tell you: you can’t be certain of the existence of any mind but your own. Everyone else, from your parents to your pets, has to be treated with at least a modicum of suspicion. There’s simply no way to know that you’re not, in fact, living in a world inhabited entirely by p-zombies.

But while can’t prove the existence (or non-existence) of another mind, we can at least quantify our uncertainty—at some level, I know my dog is more likely to be conscious than a rock.

This is the idea behind the famous Turing Test. A subject is allowed to communicate, via text, with both a machine and another human. To the degree the machine is able to convince the subject of its humanity, we must grant that it is able to “think”.

This isn’t the most scientifically satisfying answer, but it at least gives us a path forward.

Self-Experimentation

Like most people, my waking mind is a constant stream of internal speech. And every night I interact with dream characters, more or less convinced of their sentience, at least in the moment.

So I figured, maybe the Turing Test can help me determine whether these voices are independent minds, or if they’re simply hallucinations.

Internal Dialogue

One easy experiment was learning to identify certain thoughts as being external. This is a common practice among certain Evangelical Christians, who learn to identify their best thoughts as being the voice of God. Tanya Luhrmann describes techniques for developing this skill in her book When God Talks Back.

I found that both positive and negative thoughts could be “externalized”. What’s more, narratizing dark, intrusive, or obsessive thoughts as originating from someone else (e.g. my Jungian Shadow) robbed them of their power—the guilt and despair that would often follow them disappeared. And externalizing my best impulses as the proddings of a higher self or benevolent divinity encouraged me to act on them.

This practice is not without its dangers. Once you’ve learned to trust certain thoughts implicitly, it’s easy to begin attributing selfish thoughts to the trusted voice. Luhrmann recalls listening to a young woman tell her congregation that God was calling her to do service work in Mexico. The man next to her smiled and whispered, “God sure seems to need a lot of work done in Puerto Vallarta.”

Dreams

Dreams have been another rich avenue for experimentation. I have the good fortune of frequently having lucid dreams—I can formulate plans before bed, and (sometimes) carry them out in my dreams. So naturally I’ve interviewed dozens of dream characters.

Dream characters (or DCs, as the lucid dreaming community calls them) often exhibit rich, complex (and, to be sure, bewildering) behavior. Their desires and values are generally orthogonal, if not counter to our own. We have no access to their internal states–they can lie to us and surprise us. Though they are presumably encoded somewhere in “my” brain, they are very much not “me”.

But are they conscious? Or are they just a collection of visual and auditory hallucinations, coordinated according to my model of human behavior?

Again, I can’t answer this question definitively. But after dozens of discussions with them, my intuition is that they do indeed have inner lives. Though their existence may only last a few minutes, they exhibit a complexity and intelligence that is hard to ignore. At times, they have demonstrated knowledge or wisdom that would be hard to attribute to my own mind (including a couple wildly specific pieces of pop culture trivia).

It would be useless for me to enumerate my dream experiences here - if you’ve ever tried to relate a particularly poignant dream to a friend, only to be met with profound disinterest, you’ll understand. Instead, I’ll leave you with one brief exchange:

Me: Are you part of my unconscious?

DC: Do you really think that’s a good word for it?

[1] In 2017, a research team studied two split-brain patients a decade after their surgery. While they failed to replicate some of Gazzaniga's findings, Gazzaniga points out several inadequacies in their research. This paper provides a brief summary of the controversy.

Join the discussion on Substack!