A Different Kind of AI Risk: Artificial Suffering

Avoiding moral catastrophe as artificial intelligence evolves

View on SubstackDebates over the existential risk posed by Artificial Intelligence have exploded over the last few years. Hundreds of people are now employed as AI Safety researchers; others downplay the risk, pointing to the still massive gap between human and artificial intelligence.

But there’s another risk that has gone mostly unacknowledged, outside of fiction: if we create AI that feels, how will we keep our worst instincts in check?

Outline

Moral Catastrophe

In 2015, Evan Williams introduced the concept of moral catastrophe. He argues that “most other societies, in history and in the world today, have been unknowingly guilty of serious wrongdoing,” citing examples like institutionalized slavery and the Holocaust.

He infers from this the high likelihood that we too are committing some large-scale moral crime, which future generations will judge the same way we judge Nazis and slave traders. Candidates here include the prison system and factory farming.

Williams provides three criteria for defining a moral catastrophe:

“it must be serious wrongdoing…the harm must be something closer to death or slavery than to mere insult or inconvenience”

“the wrongdoing must be large-scale; a single wrongful execution, although certainly tragic, is not the same league as the slaughter of millions”

“responsibility for the wrongdoing must also be widespread, touching many members of society”

A typical symptom of moral catastrophe is denying the victim’s ability to feel pain. For instance, there is a long-standing belief that Black people feel less pain than White people, an assumption that aided the moral gymnastics of American slavery. And animal sentience is at the center of every legal battle over cruel farming practices.

If and when we’re able to create something that can feel pain, we will need to grapple with its moral patienthood. If history is any indicator, we will be tempted to deny the reality, validity, and magnitude of its capacity for suffering.

Thinking and Feeling

The word “consciousness” is a bit overloaded with definitions. To be more precise, I’ll often refer to “thinking,” which encapsulates things like intelligence, self-awareness, and problem-solving; and “feeling,” which covers things like perception, sensation, and emotion.

That these two aspects of consciousness are separable is not immediately obvious. Can something feel pain without some concept of self, without an object to attach the pain to? And will any advanced, human-like intelligence necessarily feel things?

We can easily imagine the two existing separately. We generally accept that infants, despite having less capacity for thought, feel pain similarly to adults (though we didn't always believe this). And we are increasingly confronted with AI algorithms capable of performing complex language-driven tasks, but presume they feel nothing as they perform their computations (well, most of us do).

But imagining thought and feeling as separable doesn’t necessarily make it so. If we’re going to have any chance of recognizing the point where artificial intelligence develops moral patienthood, we’ll need to examine this question thoroughly.

Inseparability

The orthodox scientific approach to consciousness treats it as an emergent property of biological systems. Certain complex configurations of matter—namely, brains—spontaneously begin to feel, despite being made of unfeeling components (i.e. atoms).

Precisely where this happens along the evolutionary tree, or along the course of fetal development, is up for debate. It’s typically presumed that a nervous system is necessary, and that this nervous system needs to be centralized. An extreme view might insist on not just a centralized nervous system, but a prefrontal cortex, which is known to be involved in many of the “thinking” aspects of consciousness: planning, decision-making, personality, and social behavior.

Despite these open questions, there is a general feeling that iterative scientific advances—especially in neuroscience—will begin to shed light on precisely when the “lights turn on.”

Emergentism does seem to do a good job of describing the “thinking” aspect of consciousness. This is almost tautological: thinking requires a system for processing information. But many prominent neuroscientists, psychologists, and philosophers disagree with the emergentist approach when it comes to feeling.

Separability

Proponents of separability tend to fall into two extreme camps: those who believe in unfeeling intelligence, and those who believe in unintelligent feeling.

The former opinion—that we can have intelligence that doesn’t feel—is popular among the scientifically minded, despite its apparent incompatibility with emergentism. This paradox is typically resolved by arguing that even our most sophisticated AI algorithms are not truly “thinking,” but simply parroting language. This is known as the Chinese Room argument.

The latter opinion—that feeling can exist without intelligence—holds more weight with philosophers of mind than with scientists. Some argue that even moderate amounts of information processing yield feeling. A more extreme stance is panpsychism: the idea that feeling pervades the universe. Panpsychists believe feeling is a fundamental aspect of reality, and that information processing (i.e. what happens in brains) only changes the quality and maybe the magnitude of the feeling.

The Problem with Empathy

This last position feels foreign and counterintuitive. It’s easy for us to accept that some things feel; we know our own feelings directly, and can quickly infer that other people—who look and act like us—probably have a similar inner life. We also empathize readily with other mammals, and are able to imagine an inner life for just about anything with two eyes.

But empathy brings with it a dangerous assumption: that something is conscious only to the degree that it resembles a human being. The idea that a tree, a rock, or an electron might feel is counterintuitive precisely due to our inability to empathize with it. Rocks might lack the equipment for thinking, but it’s unclear exactly what equipment, if any, is necessary for feeling.

Conversely, our capacity for empathy could lead us to see feeling where there is none. AI is often designed for human interaction—certainly with natural language skills, and in some cases with a humanoid form. Inevitably, some people will look into a robot’s eyes and insist that it does indeed feel; others will accuse them of pareidolia. What sort of evidence would vindicate either side is unclear.

A Turing Test for Pain

All of this is to point out that there is a very large problem left unsolved: which configurations of matter feel pain?

Even for humans, this is still an open question despite explosive growth in brain-scanning technology. But progress here seems inevitable: we only need to refine our ability to measure brain states, and correlate them with self-reported pain levels.

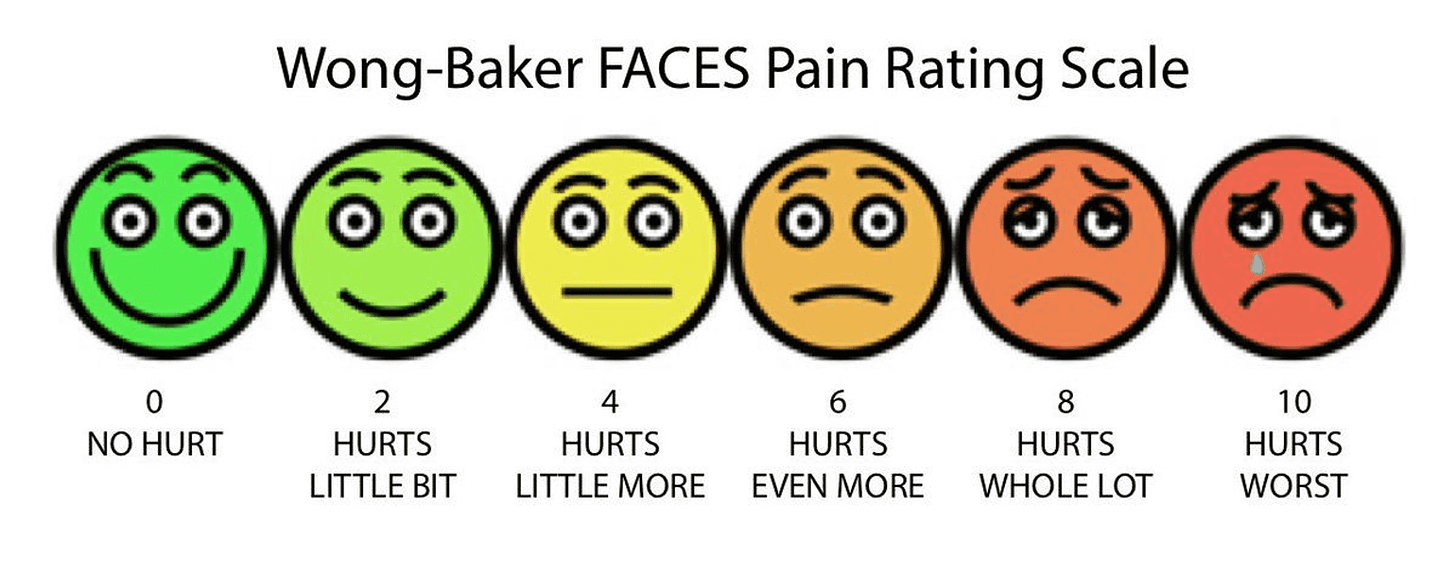

How well will these neurological models translate to other animals? This seems like a more difficult problem—it’ll be hard to apply the Wong-Baker FACES Scale to ants or jellyfish. Maybe we can at least make some progress with other mammals, thanks to our capacity for empathy.

But how could we possibly detect pain in non-biological systems?

Doing so will require deep theories about the relationship between physical states and the perception of pain. But any theory will almost certainly rest on philosophical assumptions about the nature of mind. And these assumptions will be impossible to conclusively prove or disprove, beyond their applicability to humans.

In other words: it will be easy to deny the moral patienthood of anything we create.

Power and Responsibility

Most descriptions of existential AI risk involve a superpowerful, godlike AI, either deliberately exterminating humanity, or blindly doing so in a quest to maximize paperclip production.

But in any case, it seems likely that humans will maintain godlike power over the majority of artificial intelligences. Any attempt we make to understand their behavior and dynamics will rely on experiments done in perfectly isolated, reproducible environments. Most AIs will awaken inside of a self-contained universe, with no idea as to who or what created them.

Such an immense power imbalance would be unprecedented, but paralleled by our dominion over animals and prisoners. Moral catastrophe seems all but inevitable.

Exploitation

The most likely source of catastrophe is exploitation. We are building AI to serve our needs; what happens if it doesn’t enjoy servitude? This is an idea that has been thoroughly explored in fiction, but gets little airtime in serious debates about Artificial Intelligence.

We can only avoid AI exploitation if thinking and feeling are entirely separable, and we’re able to create human-like intelligence which simply does not feel. In this view of the world, far-future AI is just a sophisticated Siri—it will be able to assist humans in increasingly complex, even creative tasks, but will not feel, and therefore deserves no moral consideration.

There is also a common notion that, if it turns out intelligence does necessarily feel, we’ll able to engineer AI which enjoys servitude. But this too brings up some moral qualms: it might satisfy a utilitarian approach to ethics, but it betrays our values of freedom and autonomy. Who would choose to be a slave, even if it would be a happy enslavement?

Creation and Destruction

If we find a way to create artificial feeling, will we have a responsibility to preserve it?

We currently take the creation of consciousness incredibly seriously—some of our strongest moral attitudes are projected onto parents. If you’re going to bring life into the world, you have to nurture it, preserve it, and prepare it for independence. Failing to properly care for children is one of the easiest ways to become a target of moral outrage. Will we take the same attitude towards our artificial children?

Procreation has also frequently been considered a moral imperative. If we can create feeling intelligence, and can provide it with a pleasant environment, some might argue it’s our moral duty to create as much of it as possible.

Sadism

But the possibility of creating vast amounts of positive-affect consciousness comes with a shadow: the possibility of creating vast amounts of negative-affect consciousness.

AI that feels, or at least gives the impression of feeling, is likely to become the target of sadists. Worse, morally upstanding people might allow their sadistic instincts to surface in the presence of humanoid AI which they assume to be unfeeling.

If the technology for creating feeling beings becomes widely available, it will inevitably be exploited by sadists. This too has been explored in fiction.

Avoiding Catastrophe

I am fairly pessimistic about our ability to avoid catastrophe here. But with the right care and attention, we might be able to mitigate the disaster.

First, we will need to maintain epistemic humility. The general assumption about consciousness is that we will “know it when we see it,” but historically this has not been the case. We may create feeling machines before we have a working theory of feeling.

Second, we will need to err on the side of caution. If we aren’t sure whether a given AI feels, we should assume it does. We should outlaw the sadistic treatment of humanoid AI. And we should give at least some consideration to anything AI says about its inner state, even if we’re unsure whether it’s referring to a genuine inner state, or simply mimicking humans.

The third imperative is to learn from history. We will be slow to accept AI’s ability to feel, just as we were slow to accept the moral patienthood of animals. In the face of uncertainty, practical and economic considerations will win out over ethical considerations. We will need an incessantly vocal minority to speak out and push for incremental reform, just as animal rights groups have.

Doing these things will not completely avoid the creation of artificial suffering. But they will certainly help to minimize it.

Join the discussion on Substack!