Suffering = Pain × Resistance

Meditative techniques for coping with physical and emotional pain. Also, math.

View on SubstackMost of us think of pain and suffering as synonymous. But many meditators—myself included—have found that there’s a way to mentally reorient towards painful sensations and suffer less.

One of the most prominent advocates for these techniques is Shinzen Young, an American meditation instructor with decades of training in various Buddhist traditions. His lesson is simple: directed attention can take the bite out of pain—even when it’s severe or chronic.

It is part of nature's wry sense of humor that the quickest way to "break up" pain is to observe it without the slightest desire that it be different in any way.

—Shinzen Young, Natural Pain Relief

Outline

Resistance

The notion of pain without suffering is a little hard to wrap your head around if you’ve never experienced it.

For most people the notion of pain which is not suffering may sound like a contradiction in terms. People have difficulty imagining what the experience of pain without suffering would be like. Does it hurt? Yes. Is that a problem? No.

People have difficulty understanding this because they are not familiar with the experience of pure pain, that is, pain without resistance…What people call "pain" is actually a combination of pain and resistance.

—Shinzen Young, Natural Pain Relief

He boils all this down into a single formula: Suffering = Pain × Resistance, defining1 the terms as follows:

Pain: “any uncomfortable sensation”

Resistance: “any push and pull, any craving and aversion that interferes with the natural flow of the pain”

Suffering: “a kind of internal civil war, a kind of pressure that develops when one part of ones being…clashes with another part of ones being”

In other words, if you don’t want to suffer, you need to make one of the two factors on the right-hand side of the equation zero: you can remove the source of pain, or your can stop resisting it. Conversely, resistance can amplify the tiniest bit of pain into unbearable suffering.

Since we often don’t have control over the pain, Shinzen focuses on cultivating equanimity—the antidote to resistance.

Techniques

In his writing and talks, Shinzen provides an intricate phenomenology of pain. The varieties are vast—from the sharp prick of a pin, to the rumbling throb of a stomach ache—but he distills some common techniques that can be explored no matter what sort of pain you’re dealing with.

The first step is to dive into the sensations and examine them. You might think this is trivial—when you’re in pain, it’s hard to think about anything else! But I’ve almost always found, upon introspection, that I’m more absorbed in a narrative about the pain than in the painful sensations themselves. I’m feeling bad for myself, wishing I felt better, mourning all the things I can’t do, while the painful sensations roil on at the edge of consciousness.

If you do direct your attention to the tactile sensations driving your pain, you’ll notice they’re surprisingly fluid, especially when compared with the fixed narrative of “I’m hurting”.

The sensation of pain shifts shape or position every few seconds, becomes stronger or weaker, expands, contracts and circulates. Flavors change; a burn becomes an itch, the itch becomes a pressure, and so on. Eventually you come to realize that even the most horrible pain is in fact made up of pure vibrant energy.

—Shinzen Young, Natural Pain Relief

Personally I find a great deal of relief only going this far. Focusing on the sensations themselves, rather than the story I’m telling myself about the pain, removes the suffering. The problem is that it’s hard to maintain focus—the second that narrative starts to edge back in, it feeds on itself, and I’m launched back into the world of suffering. And there’s certainly no way to keep my attention sufficiently focused if I need to work, or just want to watch TV.

Fortunately Shinzen recommends a technique called “zooming” to provide more lasting relief. I’ve only just started experimenting with this, and it seems to work well.

First, you need to identify the area of most intense pain. If you’ve got a specific injury, it’ll probably be exactly at that spot; if you’re dealing with something more subtle, you’ll need to introspect to find its center of gravity.

Typically, there will be places within a sensation that are intense and other places that are less intense. Typically the less intense is around the border, the more intense is at the center. But it doesn't necessarily have that kind of spatial configuration.

—Shinzen Young, Zooming

What you’ll find is that, branching out from that central locus, there are waves of secondary sensations emanating in all directions. You might feel the pain rolling through your limbs or torso, spreading through your head, and even emanating out into the space around your body.2

Often, you will be able to detect that in addition to the local obvious sensation, there are subtle influences that spread from that. It could be that you get a spread that is continuous from the primary, but more frequently you get a little ping here, a little ping there, a little ping there. Or you may not be aware of any spread at all.

—Shinzen Young, Zooming

According to Shinzen, this is where the majority of suffering occurs—in these spreading secondary sensations:

Most of the suffering is not in local intensities. Most of the suffering is in the resistance to the subtle spread, particularly the resistance to the spread that is below the threshold of awareness. It's resistance to very, very, very tiny sensations. So tiny that the surface consciousness is not aware of them. The resistance to the subtle spread through the body, until it's been trained away, is huge. Those tiny little sensations catch in the gears of the nervous system. That's why people's bodies shake and so forth. And that's actually where most of the suffering is.

—Shinzen Young, Zooming

To break through this resistance, Shinzen encourages students to practice zooming in and zooming out.

“Zooming in” means focusing on a small part of the sensation—either the central locus or some secondary emanation—and keeping your attention there for at least a few seconds. Again, this alone can provide some relief, since you’re only dealing with one small part of the pain.

“Zooming out” means spreading your awareness across the entire set3 of sensations. This too can provide some relief—the intensity of the pain seems to subside as you increase the area of attention. Shinzen relates this to the Ideal Gas Law of physics:

It's sort of like the laws of physical chemistry: Pressure is inversely proportional to volume. So if you give it volume, you may find that helpful.

—Shinzen Young, Zooming

Finally, the real trick is to zoom in and out at the same time. This is something I still struggle to do effectively, but I find it very compelling.

The zoom in, in this case, means you intentionally go to the most intense part you can find. And the zoom out, in this case, means you simultaneously spread your awareness as broadly as you can through the body.

…If you go local and at the same time spread your attention over the whole body, that tends to grease the rails for the spread to occur without resistance.

…Zooming in and out at the same time…will lead to a kind of experience of splash, ripple through the body, radiate beyond the body into the infinity of space and dissipate. You tend to get that rhythm: splash, ripple, filling the body, then radiation out, and release.

—Shinzen Young, Zooming

Corollaries

I can’t help but note how closely Shinzen’s “zooming” instructions track with the concepts of “narrow and wide attention” that I explored in How to Enjoy Things. And Shinzen does extend his insight beyond pain management: he says it applies equally well to pleasure.

I might add that most people are also not familiar with the experience of pure pleasure. What people call "pleasure" is actually a mixture of pleasure and grasping. Just as consciousness is purified by experiencing pain without resistance, it is equally purified by experiencing pleasure without grasping.

—Shinzen Young, Natural Pain Relief

He also repeatedly states that the same techniques can be applied to emotional pain.

This is a bit trickier to grasp—we don’t really think of emotions as having a spatial locus and spread inside the body. But I’ve found that usually, if I spend enough time scanning my body, I can find a spot (often, but not always, around my stomach) that corresponds with the emotion. I’ve heard one advanced meditator claim that every feeling and emotion has a tactile correlate, and that you can dissolve it using Shinzen’s techniques.

My Own Experience

I’ve been playing with the experience of pain in meditation for several years, and Shinzen’s teachings have helped me refine what I learned through raw experience. During the writing of this essay, I also had two well-timed opportunities to explore his ideas more deeply:

On the advice of a friend, I purchased a Shakti mat, the trendy modern equivalent of a bed of nails

On the advice of no one, I contracted COVID, and have been dealing with all the resulting aches and pains and discomfort

First the Shakti mat: I don’t know if I could have survived the first use without the techniques above. It hurts! And I’m only on their middle-tier option. But by zooming in on the pain and feeling the sensations themselves, instead of the panicky narratives rushing into my head (am I doing damage to my back? did it break the skin?!) I was able to power through the first session.

More interestingly, by developing a vocabulary for the sensations the mat causes—initially thousands of dots of prickly static, followed by a warm, pulsating glow—I got used to it very quickly. Now I’m able to settle in after 15-30 seconds instead of 4-5 agonizing minutes. This sort of habituation would probably happen with or without Shinzen’s techniques, but I’m fairly certain they sped up the process.

The COVID-related pain is more interesting. Often I’m dealing with multiple areas at once—say stomach pain and a headache. Trying to focus on either one alone doesn’t really seem to work for an extended period of time; it’s like playing whack-a-mole.

What’s interesting is that, in deep meditation, I was able to see both pains as part of the same field of tactile sensations. I could feel two central loci, but their secondary emanations bled into one another. I found that if I stopped conceiving of them as separate, I could do Shinzen’s exercises, and the pain would dissipate.

Amazingly, I could sit for a couple hours without any suffering, or even feeling the “pure pain” Shinzen describes—I was able to get lost in the steady equanimous vibe I’m used to. Of course, the second I got up, my head would throb and my joints would ache, but I found total respite while sitting in meditation. (This is similar to the relief it’s given me during minor depression.)

I often wonder how far I could take these skills. I don’t think I could withstand torture (or, like Barbara McClintock, oral surgery) at my current level, but it’s not hard for me to see how others might. And I’d like to think that if and when I am challenged with extreme pain, I’ve gathered the right tools to help me cope.

Addendum: The Math

I find Shinzen’s use of mathematical and physical language alluring. It gives his phenomenology an air of rigor—even if he isn’t always rigorous in applying it.4 Let’s explore his formula and see if we can learn more about what’s going on here.

First: since the equation is a product, we should be able to flip the sign on any two terms, and still maintain equality. For example, 6 = 2 × 3 implies three other equations:

6 = -2 × -3

-6 = 2 × -3

-6 = -2 × 3

Shinzen actually does something like this, listing out four equations he calls “The Fundamental Theorem of Human Happiness”:

Suffering = Pain × Resistance

Frustration = Pleasure × Grasping

Empowerment = Pain × Equanimity

Satisfaction = Pleasure × Equanimity

This doesn’t look quite as neatly symmetrical as our numerical equations above—Shinzen has given different words for asserting your will against pain (“Resistance”) versus towards pleasure (“Grasping”), as well as a unique label for each combination of (what I’ll call) Valence and Willfulness.

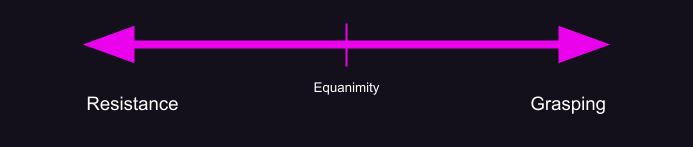

We also have two competing concepts of “negative Resistance”: Equanimity and Grasping. This is probably worth exploring.

If we treat Equanimity as “negative Resistance/Grasping”; the zero-point of this line doesn’t seem to have much meaning:

But Equanimity, in my experience, is a zero, an absence of something. I think a better model puts Equanimity at the zero-point on a continuum between Resistance on the left, and Grasping on the right, which I’ll call Willfulness.

We can still recover a concept of “high equanimity” with a conversion like:

If we look back at Shinzen’s equations, we see that high Willfulness (either positive or negative) is associated with negative emotional states; Equanimity, or zero-Willfulness, is associated with positive states. The valence of the underlying impulse doesn’t even seem to matter!

But of course it matters—I’d rather be equanimously having sex than equanimously on fire.5 And Shinzen does seem to differentiate between “pure pain” (Empowerment) and “pure pleasure” (Satisfaction), the different feelings that arise in a state of zero-Willfulness.

I think the only reasonable way to resolve this paradox is to admit that the left hand side of the equation—call it Emotional State—is multidimensional. Even if we can represent Valence and Willfulness as single6 numbers, we can’t simply multiply them together and retain all the information we need about Emotional State.

I love the idea of mathematizing phenomenology, and would like to find a way to more succinctly express Shinzen’s four equations of The Fundamental Theorem of Human Happiness. But even Shinzen himself says that they’re only “linear approximations” for something more complicated, and points to the work of S. S. Stevens on power law distributions in pain perception.

Maybe if enough mathematicians and theoretical physicists take up meditation, we’ll get a more formal description of the phenomenology of pain and pleasure. For now we’ll have to be content with these simple-but-imperfect equations, and infer what we can from them.

I often have tactile sensations that—proprioceptively—occur outside my body. Obviously I’m not physically feeling something in the air around me, but my brain’s body-map paints these sensations as if they were extended 1-2 feet from my physical body. When people talk about “auras” and “qi” and such, I assume this is what they’re referring to.

Shinzen doesn’t say this explicitly, but for me it means spreading my attention in both space and time—I focus on the temporal dynamics of the pain as well as its spatial orientation.

It’s never entirely clear how metaphorically Shinzen is speaking with his equations. At one point he calls them “approximations” (which might imply metaphor) and at another “linear approximations” (which has a technically precise meaning). We should probably take his (and my) mathematical assertions with a grain of salt.

Part of me wonders if this is in fact true. The difference might disappear with perfect equanimity.

I suspect Valence might have a small number of dimensions, but I agree with QRI that it likely corresponds with the symmetry or periodicity of the impulse.

Join the discussion on Substack!