Contra Ozy Brennan on Ameliatarianism

Constructing an ethical diet is hard. Utilitarian morality isn't the answer.

View on SubstackOzy Brennan recently posted a thoughtful essay pointing out a paradox in ethical eating: consuming small, low-intelligence animals like fish and chickens creates more suffering than eating large, high-intelligence mammals like pigs and cows. They advocate for a diet that restricts poultry and seafood, but allows beef and pork.

I find this distressing. I’ve adopted a mostly pescatarian diet with the goal of reducing animal suffering, and Ozy is saying I got it backwards. But also I love beef and pork and would readily accept any reason to order a steak instead of the haddock. So (if you’ll excuse the pun) I dug in.

Unfortunately, I think Ozy is wrong. The reasons why are interesting, and provide a lens for examining the limits of Utilitarian ethics.

Outline

Capacity for Suffering

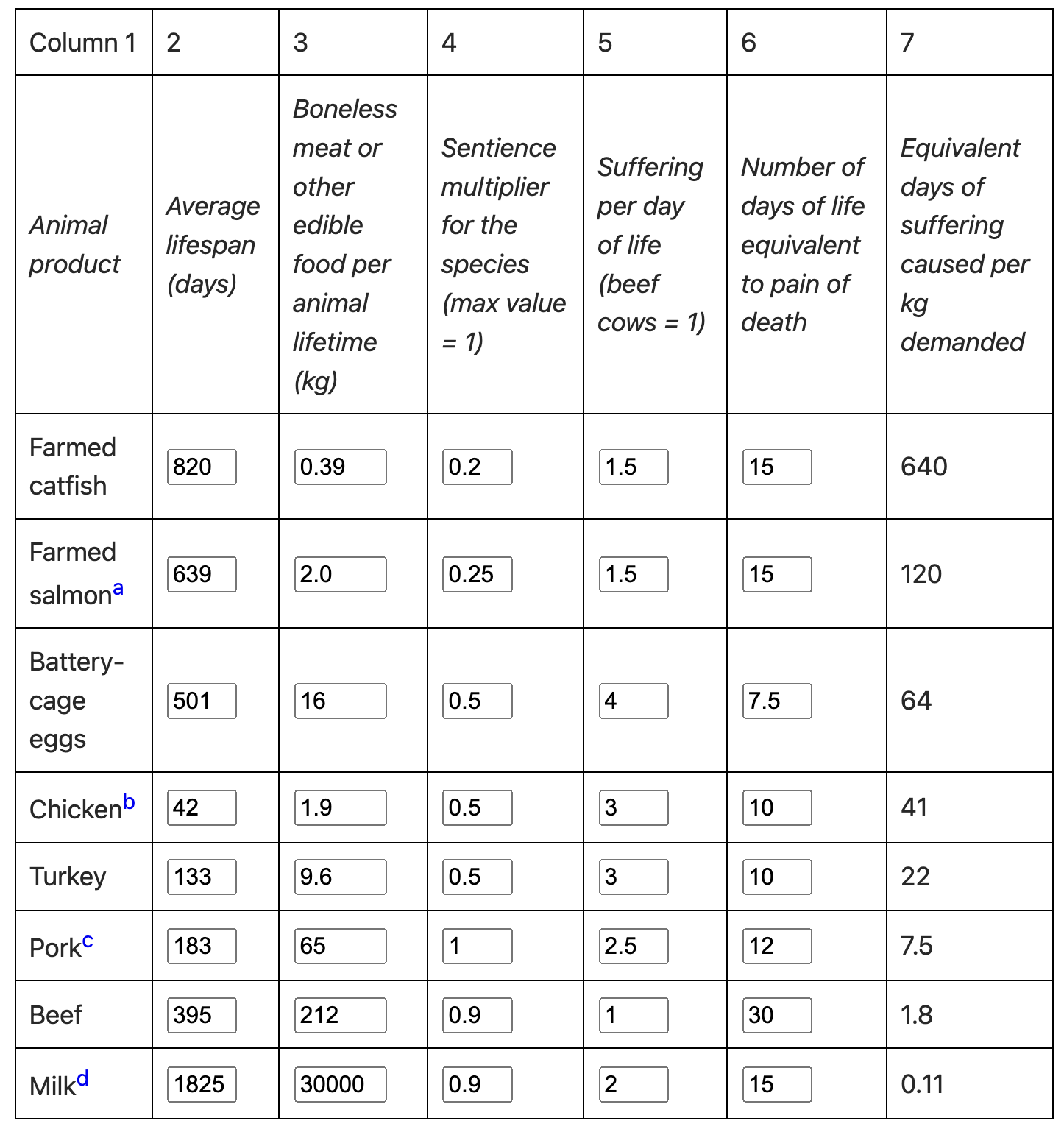

Ozy’s argument is inspired by a fascinating suffering calculator developed by Brian Tomasik. Brian asks us to consider the “suffering per kilogram”1 of our food:

Using Brian’s default numbers, pork, beef, and dairy—three delicious foods I’ve mostly removed from my diet—produce very little suffering. Farmed fish—which I eat without reserve—produces 350 times more suffering per kilogram than beef.

Two major caveats here:

The “sentience multiplier” column represents a more-or-less random assumption on the author’s part. He admits as much and suggests maybe using brain size as a proxy.

The “suffering per day” metric is also very subjective, but at least informed by Brian’s knowledge of farming conditions for each type of animal.

I mostly trust the latter numbers—Brian’s knowledge here is deeper than mine. But I take a lot of issue with his numbers for the former.

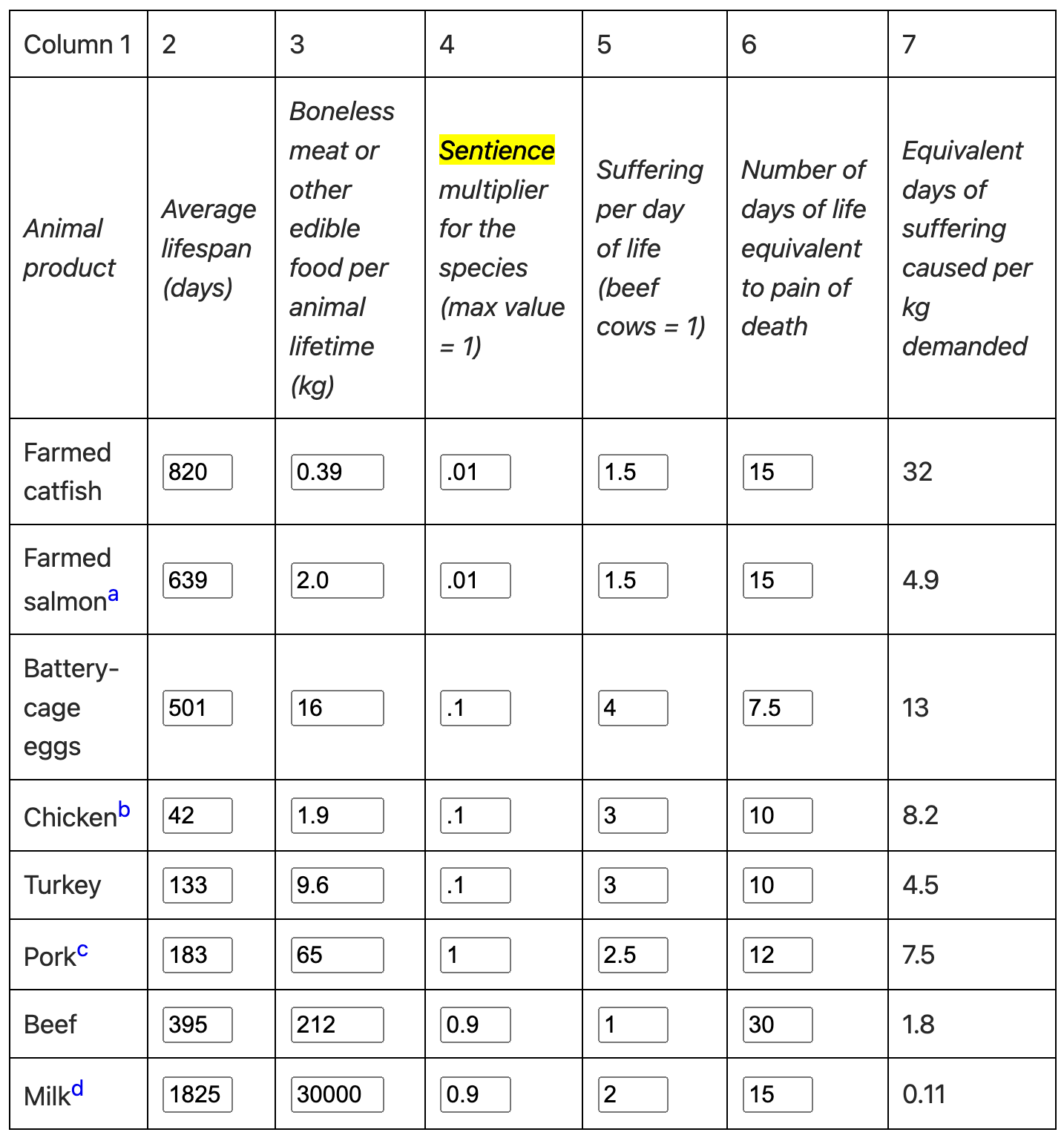

I think sentience likely operates on a log scale (also a more-or-less random assumption on my part, driven entirely by intuition). Let’s see what happens if we decide pigs are 100x more sentient than fish, rather than 5x:

The numbers are a little more ambiguous now, but farmed catfish are still the worst thing you can eat, by far! Eating catfish produces 4x more suffering than eating chicken, which in turn produces 4x more than beef. This is still completely backwards from my diet.

At this point I was getting ready to order a hamburger.

Repugnance

Here’s a thought experiment to help us recalibrate:

Say there are a billion people who all have a papercut, and one person with a cluster headache. With the push of a button, you can either cure all the papercuts, or you can cure the headache. What do you do?

Instinctively, I’d help the person with the headache. I believe this is the morally preferable answer, no matter how many papercuts there are.

Utilitarian ethics disagrees—the sum of the suffering felt by all the papercut people exceeds the suffering felt by the one person with a headache2. The right thing to do is cure the papercuts.

Hardcore Utilitarians would say the utility calculation helps us avoid a natural bias. Maybe we struggle to grok the number “one billion” properly, since we don’t have much intuition for anything that big; or maybe our sense of empathy is miscalibrated towards individuals over groups. They’d say we need utilitarian calculations to make up for these sorts of biases—and in many cases they’re right.

But the Utilitarian line of thinking leads to all sorts of nonsense.

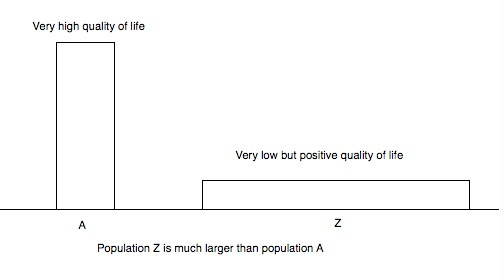

You might recognize the thought experiment above as a variation on the Mere Addition Paradox, aka the Repugnant Conclusion: according to Utilitarian ethics, it’s better to have 100,000 people who are barely happy to be alive than 1,000 deeply satisfied people, since the former leads to more total happiness.

In other words: a naive Utilitarian ethos would rather have billions of people with lives barely worth living than a small society of very happy people.

There are some interesting responses3 to this paradox that claim to solve it without abandoning the Utilitarian notion of a quantified ethics, like considering average utility, or a mixture of average and total utility. But they all lead to their own paradoxes with fun names like the “Absurd Conclusion” and the “Sadistic Conclusion”.

At most levels of scale, it makes more sense to help those suffering the most before we consider aggregate happiness.

Does Not Compute

An hypothesis: maybe morality can’t be quantified.

More specifically, maybe there’s no single mathematical framework for judging ethical decisions, and the best we can do is appeal to multiple overlapping-but-contradictory models, and live with the ambiguity that creates.

Utilitarians seem to find this idea more repugnant than a mega-civilization of barely-not-suicidal people. It’s tantamount to heresy in a lot of Rationalism-oriented places. There was a time when I too would have found this idea deeply uncomfortable, like learning there’s a contradiction at the heart of Mathematics, or that the laws of Physics change whimsically over time.

It’s distressing because it leaves us with no hope of knowing whether we’re right or wrong, or of even being conclusively right or wrong. It betrays the Enlightenment Era faith that the universe is ultimately knowable. It replaces the steady march of intellectual progress with a dance along a road to nowhere.

And it’s natural to fear the opposite extreme: without an absolute method for judging morality, we might end up adrift in a sea of moral relativism, where anything is permitted.

But as we’ve seen before, this would be falling into the trap of black-and-white thinking. Denying the existence of a single, final measure of morality doesn’t mean we can’t have a few good provisional measures. There’s plenty of room between pure Absolutism and pure Relativism.

There are still Utilitarian lessons we can draw here: taking lifespan into account is helpful, and has me reevaluating my diet. I’m going to start seeking out wild-caught fish, rather than leaning on my deontic crutch of “fish good, beef bad”.

But in the end, I’ll continue to rely on a combination of Utilitarian, Deontological, and Intuitive ethics. I’ll keep regularly eating fish, occasionally eating poultry, very occasionally eating pork and beef, and never eating humans.

And I’ll remain open to arguments, Utilitarian or otherwise, that might help me become a better person.

It’s worth reading the Limitations section of Brian’s article, where he acknowledges a few of my criticisms, and says we shouldn’t take his numbers too seriously.

If you think a cluster headache is more than a billion times worse than a papercut, you can adjust the number of people and severity of symptoms as necessary.

See also: Schrödinger’s concept of intersubjectivity as an explanation of the paradox

Join the discussion on Substack!