Church of Reality: Ernst Mach on Mind, Matter, and the Illusion of Self

"The ego must be given up."

View on SubstackThis post is part of a series on the philosophical and spiritual views of prominent scientists and mathematicians. Past subjects include Erwin Schrödinger, Max Planck, and Barbara McClintock. Future subjects will include Albert Einstein, David Bohm, and William Clifford.

Ernst Mach—best known for his work on the speed of sound—wanted to remove any trace of metaphysics and philosophy from science. Naturally, this led him to develop an extensive metaphysics and philosophy of science.

But Mach’s metaphysical scheme proved powerful. His work potentiated huge leaps in physics—he influenced many of the founders of quantum mechanics (including Heisenberg and Pauli), and Einstein credited him as an inspiration for relativity.

Interestingly, Mach’s philosophy shares a lot with Eastern mysticism—he’s even been called the “Buddha of Science”1. Let’s see why his ideas were so important to 20th century physics, and why they’re still met with resistance today.

Outline

The Analysis of Sensations

Map and Territory

The Elements

No Essence

No Self

Mach’s Legacy

The Analysis of Sensations

Mach was deeply introspective. The peripheral sensations that most of us become inured to—like the tip of your nose protruding into your vision—Mach remained intensely aware of. In his book The Analysis of Sensations, he draws from both contemporary science and his own experience to deliver a brilliant investigation into the physiology and phenomenology of perception.

We might compare Mach’s attitude with modern-day mindfulness2. But it was an intensely scientific mindfulness—he dug into the core of each sensation, hoping to understand its dynamics.

Mach wanted to build a bridge between his two academic passions: physics and psychology3. While he agreed that both domains spring from the same underlying reality, he broke from many of his peers by doubting that psychology could be reduced to physics, at least as it stood.

Physics, despite its considerable development, nevertheless constitutes but a portion of a larger collective body of knowledge…it is unable, with its limited intellectual implements, created for limited and special purposes, to exhaust all the subject-matter in question.

He was particularly frustrated by the attitudes of his fellow physicists, who insisted on the primacy of their field.

I was lectured by a physicist on the misguided way in which I had conceived my task. In his opinion, it was impossible to analyze the sensations as long as the paths of the atoms in the brain were unknown; and when they were known everything else would follow of itself...he4 too, like countless others, took the instruments of a special science to be the actual world.

Map and Territory

Mach’s main complaint was that we’re too quick to equate our models of reality with reality itself—we confuse the maps we build with the territory our maps describe. He saw every concept as a useful fiction, invented in the service of a particular goal.

The…conceptions of the average man of the world are formed…not by the full and pure desire for knowledge as an end in itself, but by the struggle to adapt himself favorably to the conditions of life.5

For Mach, the territory is sensation: sounds, colors, shapes, smells. Everything else—dogs, atoms, equations—can be seen as a map describing a particular set of sensations and the relationships between them. Concepts compress a large, fuzzy section of sensation-space into a single word; the word then conjures up the relevant sensations when read or heard.

Mach points out that this is a lossy compression scheme—it packs an effectively infinite number of sensory impressions into a few bytes of data. Decompression—moving backwards from words to sensations—results in a blurry, incomplete picture.

A universal triangle, which is at once right-angled and equilateral, cannot be imagined…generally, words, being designations which…describe many particular presentations, are far from corresponding completely to any concept.

Most of the time, this doesn't matter. If I tell you I have a "large brown dog", you don't need to know his precise weight or the exact shade of brown to get a reasonable sense of the situation. And if these details become important, I can always get more specific. Mach admits as much:

…the specialist, the physicist, for instance, has no reason to allow himself to be troubled overmuch by such speculations…His conceptions, in so far as they prove to be inadequate, will be best and most quickly corrected by the facts…Every physicist is not an epistemologist, nor ought every physicist to be one, even if it were possible.

But for a generalist like Mach, who wants to build a worldview that can span multiple domains, epistemology becomes immensely important. The concepts from one domain can obscure details that are important to the other.

But when it is a question of bringing into connection two adjacent departments, each of which has been developed in its special and peculiar way, the connection cannot be effected by means of the limited conceptions of a narrow special department. By means of more general considerations, conceptions have to be created which shall be adequate for the wider domain.

So rather than trying to model psychology as “applied physics”, Mach wanted to step back and develop a new ontology—one that could serve as a foundation for the entire edifice of Science.

I only seek to adopt in physics a point of view that need not be changed the moment our glance is carried over into the domain of another science; for, ultimately, all must form one whole.

A modest goal.

The Elements

Mach’s solution is simple but profound. Since every word stands for a cloud of sensory experiences, why not put sensory experience at the root of our ontology?

For us, colors, sounds, spaces, times…are provisionally the ultimate elements, whose given connection it is our business to investigate. It is precisely in this that the exploration of reality consists.

In Mach’s scheme, sensations are the “elements” of the world, its basic building blocks.

These elements—elements in the sense that no further resolution has as yet been made of them—are the simplest materials out of which the physical, and also the psychological, world is built up.

This is the core of Mach’s philosophy, and it’s a difficult point to grok.

His approach clearly deviates from the typical materialist scheme, where the “elements” are things like atoms, quarks, or strings. But he also distinguishes it from Idealist philosophies, where the world is purely mental. Mach’s elements are neither internal/subjective, nor external/objective—they transcend the distinction.

There is no rift between the psychical and the physical, no inside and outside, no “sensation” to which an external “thing,” different from sensation, corresponds. There is but one kind of elements, out of which this supposed inside and outside are formed…The world of sense belongs both to the physical and the psychical domain alike.

Setting aside the metaphysics6, there’s a powerful simplicity to Mach’s philosophy. As Kant pointed out, sensations are the only thing we can access directly—everything else is hypothetical, derived from sensory impressions. And Mach further contends that

…what we want to know is merely the dependence of experiences on one another.

and later:

…every practical and intellectual need is satisfied the moment our thoughts have acquired the power to represent the facts of the senses completely.7

In other words, there’s no need to discuss anything other than sensation. If we can describe what we see now, and find rules for predicting what we’ll see next, every theoretical and practical problem is solved, with no need to appeal to any external atoms or planets or stars.

Conversely,

…auxiliary conceptions would be devoid of value, could we not reach, by their help, the graphic representation of the sense-given facts…All auxiliary conceptions, laws, and formulae, are but quantitative norms, regulating my sensory representation of the facts. The latter is the end, the former are the means.

So higher-order concepts are still useful! While we could create equations that trace the movements of dots in the night sky, the situation becomes much simpler when we model them as a solar system.

But Mach insists that this is only a model for predicting particular sensations: what we’ll see in the night sky, or what an astronaut would hypothetically see from space. It’s not something to be taken literally—the solar system is a map, not the territory. And it’s just one of many possible maps.

Unless we subject ourselves to a certain compulsion, we see the earth as standing still, and the sun and the fixed stars in motion. This way of looking at the matter is not merely sufficient for ordinary practical purposes, but is also the simplest and most advantageous. But the opposite view has established itself as the more convenient for certain intellectual purposes…both are equally correct and equally well-adapted to their special purpose [emphasis mine]

Mach takes this to an extreme: even concepts like atoms, energy, and matter are suspect—they’re just maps of correlated measurements.

If ordinary "matter" must be regarded merely as a highly natural, unconsciously constructed mental symbol for a relatively stable complex of sensational elements, much more must this be the case with the artificial hypothetical atoms and molecules of physics and chemistry. The value of these implements for their special, limited purposes is not one whit destroyed. As before, they remain economical ways of symbolizing experience. But we have as little right to expect from them…more enlightenment and revelation than from experience itself.

He sees this approach as crucial to constructing a more powerful science—especially one that can bridge the gap between concepts like “mind” and “matter”:

Indeed, it is by regarding matter as something absolutely stable and immutable that we actually destroy the connection between physics and physiology.

No Essence

Mach’s ontological shift cuts through the Gordian Knot of Kant’s paradox: that all our knowledge is mediated by perception, and we can never know a “thing in itself”. Under Mach’s scheme, there is no “thing in itself” separate from our sensations.

The assertion, then, is correct that the world consists only of our sensations. In which case we have knowledge only of sensations, and the assumption of the nuclei [thing in itself] referred to…turns out to be quite idle and superfluous.

Mach grants that concepts are still useful, so long as we can ignore their internal motions and mechanics, their deviations from a Platonic Ideal. If, for all practical purposes, these deviations are unimportant, then we can treat a body as if it were a fixed unity.

For example: if we want to model the location of the sun in the sky, we don’t need to know about the timing of every coronal mass ejection, or take into account the fact it loses 12 trillion grams of mass every second. But again, in making these simplifications and treating the sun as a fixed object, we obscure reality.

A body is one and unchangeable only so long as it is unnecessary to consider its details. Thus both the earth and a billiard ball are spheres, if we are willing to neglect all deviations from the spherical form, and if greater precision is not necessary. But when we are obliged to carry on investigations in orography or microscopy, both bodies cease to be spheres.

This might seem like common sense—we all know that we can zoom in on something to get more detail. But most of us assume that there’s some final level of granularity, that if we could zoom in enough we’d be able to grab hold of some atomic building block. But Mach asserts there is no end—every concept we grasp turns to sand.

The man of science is not looking for a completed vision of the universe; he knows beforehand that all his labor can only go to broaden and deepen his insight. For him there is no problem of which the solution would not still require to be carried deeper

It’s here that Mach’s philosophy starts to sound like Buddhism. Mach’s assertion that concepts obscure the internal dynamics of the thing described might remind you of the Buddhist concept of anicca, or impermanence. From Wikipedia:

All temporal things, whether material or mental, are compounded objects in a continuous change of condition, subject to decline and destruction. All physical and mental events are not metaphysically real. They are not constant or permanent; they come into being and dissolve.

Compare to Mach:

Really unconditioned constancy does not exist…We attain to the idea of absolute constancy only as we overlook or underrate conditions, or as we regard them as always given, or as we deliberately disregard them.

It’s not a one-to-one match—the Buddhist doctrine places more emphasis on temporal changes, especially “decline and destruction”; Mach puts more emphasis on how language tricks us. But both insist on the unreality of the “thing in itself”—they assert that everything we gloss into a unified object is, under the hood, a continuously changing composite.

But the principle of non-essence doesn’t just apply to planets and atoms. It applies especially to our most cherished concept: selfhood.

No Self

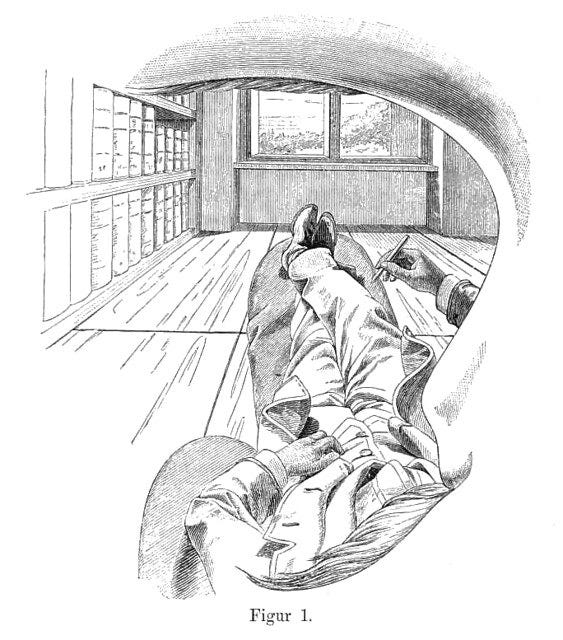

In his late teens, Mach had a classic ego dissolution experience:

On a bright summer day in the open air, the world with my ego suddenly appeared to me as one coherent mass of sensations, only more strongly coherent in the ego.

Mach speaks of this experience in terms of revelation—in an instant, he was able to see past Kant’s philosophy, which had left a major impression on him a few years earlier:

…the superfluity of the role played by "the thing in itself" abruptly dawned upon me...the actual working out of this thought did not occur until a later period, yet this moment was decisive for my whole view.8

Mach uses a bunch of Latin and Greek letters to add technical rigor to this idea. He shows there is a continuum of “elements” that range from internal (thoughts and emotions) to external (the sound of the wind or the shape of a tree), with bodily sensations in the middle.

But, Mach asserts, there’s no clear line of demarcation between these categories.

Even if we set aside Mach's elements and move back to the materialist view, it's impossible to define precisely which atoms comprise "you" versus "your environment". Sure, a neuron in your brain can be safely put in the "you" category, while the screen in front of you is obviously "environment". But what about a photon that's entering your pupil and hasn't yet hit a photoreceptor? What about an oxygen molecule passing through your nostril? At what point does the bread in your mouth go from being "food" to being "you"? The answers are a matter of definition, not fact.

The situation becomes even more nebulous when we start to think in terms of sensations rather than atoms.9

…the ego nowhere ceases. In conformity with this view the ego can be so extended as ultimately to embrace the entire world. The ego is not sharply marked off, its limits are very indefinite and arbitrarily displaceable.

For Mach, the concepts of self and other, subjective and objective, internal and external, are no different from concepts like atoms, triangles, and planets. They’re useful fictions—practical, but misleading.

As soon as we have perceived that the supposed unities "body" and "ego" are only makeshifts, designed for provisional orientation and for definite practical ends (so that we may take hold of bodies, protect ourselves against pain, and so forth), we find ourselves obliged, in many more advanced scientific investigations, to abandon them as insufficient and inappropriate.

Again, the parallels with Buddhist philosophy are hard to ignore: Mach’s conception of ego is closely related to anattā, the Buddhist doctrine of non-self. It’s still not one-to-one, but the outlines broadly match up.

Mach believed the acceptance of this fact—that there is no permanent, delineated self—would unlock whole new vistas of science10.

Our body, like every other, is part of the world of sense; the boundary-line between the physical and the psychical is solely practical and conventional. If, for the higher purposes of science, we erase this dividing-line, and consider all connections as equivalent, new paths of investigation cannot fail to be opened up.

Mach’s Legacy

Mach had high hopes for his philosophy. He believed it could serve not only as the basis for scientific advancement, but also for a more enlightened culture11.

The ego must be given up. It is partly the perception of this fact, partly the fear of it, that has given rise to the many extravagances of pessimism and optimism, and to numerous religious, ascetic, and philosophical absurdities. In the long run we shall not be able to close our eyes to this simple truth…In this way we shall arrive at a freer and more enlightened view of life, which will preclude the disregard of other egos and the over-estimation of our own. The ethical ideal founded on this view of life will be equally far removed from the ideal of the ascetic…and from the ideal of an overweening Nietzschean "superman," who cannot, and I hope will not be tolerated by his fellow-men.

Unfortunately Mach’s ideas haven’t really permeated into the broader culture. But they did leave a huge mark on science.

Mach’s main contribution was his phenomenological approach to physics. Instead of asking about what’s “really happening” out there, Mach pushed physicists to speak only in terms of measurement: what sorts of things might an observer see or hear?

You can see this influence in any of Einstein’s thought experiments, including his most famous one:

I got the happiest thought of my life in the following form:…for an observer in free-fall from the roof of a house there is…no gravitational field. Namely, if the observer lets go of any bodies, they remain relative to him, in a state of rest or uniform motion, independent of their special chemical or physical nature. The observer, therefore, is justified in interpreting his state as being "at rest."12

The doctrine of non-essence is also present in many of the category-bending ideas that emerged in the 1900s: mass and energy, space and time, wave and particle—all these pairs seemed separate, yet turned out to be the extremes of a murky continuum.

And quantum mechanics provided a deep validation of Mach’s philosophy. It elevated measurement (i.e. sensation) to a physical concept, and forced us to abandon13 the notion that the universe is in a definite state independent of those measurements. It’s impossible to say precisely where a photon was when it passed through a two-slitted screen; there is no particle-in-itself to pinpoint.

But for me, Mach’s most enduring contribution is his refusal to accept inherited notions of truth, no matter how practical or self-evident they seem. Instead he labored, against heaps of criticism, to articulate a new philosophy—one more amenable to his experience of the world. And the ontological shift he created in a few brilliant minds led to some of the greatest science ever produced.

But before I overhype Mach’s philosophy, he’d remind us not to take his map too literally. As he put it:

No point of view has absolute, permanent validity. Each has importance only for some given end.

Sources

By philosopher Heinrich Gomperz. Surprisingly, Mach didn’t protest, despite a mostly anti-religious attitude.

I can’t help but note—Mach’s mindfulness even led him to lucid dreaming, well before that was a widely recognized concept:

At a time when much engrossed with the subject of space-sensation, I dreamed of a walk in the woods. Suddenly I noticed the defective perspective displacement of the trees, and by this recognized that I was dreaming.

I also found this delightful quote:

…in dreams the ego can be very indistinct, doubled, or entirely wanting

Mach was what I’d call an active dreamer.

Mach likely would have said “physiology” rather than “psychology”, and Analysis of Sensations plays in a gray area between the two fields. He’s not so much concerned with neuroscience or personality types as he is with what he calls the “psychical domain”.

This “he” refers to a different person with a similar opinion.

Compare to Donald Hoffman’s ideas. Worth noting that Hoffman, in contrast with Mach, does assert the existence of a reality underlying and apart from our sensations.

Mach spends a great deal of time defending his ideas against labels like Idealism and Panpsychism. E.g.

…anyone who, in spite of repeated protests from myself and from other quarters, identifies my view with that of Berkeley [an Idealist], is undoubtedly very far removed from a proper appreciation of my position…And connected with this is the fear of panpsychism, which at the same time seizes my readers. Many are the victims that fall a prey to panpsychism, in the desperate struggle between a monistic conception of the universe and instinctive dualistic prejudices.

His approach seems closest to dual-aspect monism, but he’d even reject this label—for Mach, there is no second aspect.

To me, Mach’s philosophy still seems Idealistic—the only way I can square it is to say he’s only building a linguistic map, and not saying anything about reality-in-itself. But he says there is no separate reality-in-itself!

My best summary of his position is “shut up and observe.” If you’re interested in the technicalities, I’d suggest looking at the source material. See also the Einstein quote in footnote 12.

The obvious retort here is to point out that the senses can be deluded (e.g. by optical illusion or pathology). Mach responds (emphasis his):

The expression "sense-illusion" proves that we are not yet fully conscious, or at least have not yet deemed it necessary to incorporate the fact into our ordinary language, that the senses represent things neither wrongly nor correctly. All that can be truly said of the sense-organs is, that, under different circumstances they produce different sensations and perceptions. As these "circumstances," now, are extremely various in character, being partly external (inherent in the objects), partly internal (inherent in the sensory organs), and partly interior (having their activity in the central organs), it can sometimes appear, when we only notice the external circumstances, as if the organ acted differently under the same conditions. And it is customary to call the unusual effects, deceptions or illusions.

The quote continues:

I had still to struggle long and hard before I was able to retain the new conception in my special subject. With the valuable parts of physical theories we necessarily absorb a good dose of false metaphysics, which it is very difficult to sift out from what deserves to be preserved, especially when those theories have become very familiar to us.

I find this is a pattern among intelligent people who develop strong metaphysical, philosophical, or spiritual views. They go along with inherited notions of material reality, until some direct experience of non-ordinary consciousness forces them to consider a wider set of possibilities. It often takes years for them to integrate the new information into their existing knowledge.

Mach’s description of how the ego extends into environment is much more interesting than the atomistic conception described here, but also much harder to grok.

When I say that the table, the tree, and so forth, are my sensations, the statement, as contrasted with the mode of representation of the ordinary man, involves a real extension of my ego…such extensions occur, as in the case of the virtuoso, who possesses as perfect a mastery of his instrument as he does of his own body; or in the case of the skillful orator, on whom the eyes of the audience are all converged, and who is controlling the thoughts of all; or in that of the able politician who is deftly guiding his party; and so on.

Compare to Andy Clark’s conception of consciousness.

I would argue that the scientific community is finally coming around to these ideas as it confronts and examines the power of psychedelic and meditative experiences, which often revolve around the no-self revelation. Right now it looks like the resulting advances will be limited to medicine and psychology, but you never know—maybe the next Einstein is on an ayahuasca retreat as we speak.

Compare to Aldous Huxley’s ideas on the social utility of ego-reduction.

In this quote from Einstein, you can see where he agrees and where he breaks from Mach. In particular, Einstein sees the invention of concepts as a noble, creative act—even if they’re not logically necessary.

[Mach] took convincingly the position that these conceptions, even the most fundamental ones, obtained their warrant only out of empirical knowledge, that they are in no way logically necessary…

I see his weakness in this, that he more or less believed science to consist in a mere ordering of empirical material; that is to say, he did not recognize the freely constructive element in formation of concepts. In a way he thought that theories arise through discoveries and not through inventions. He even went so far that he regarded "sensations" not only as material which has to be investigated, but, as it were, as the building blocks of the real world; thereby, he believed, he could overcome the difference between psychology and physics. If he had drawn the full consequences, he would have had to reject not only atomism but also the idea of a physical reality.

Now, as far as Mach's influence on my own development is concerned, it certainly was great…

At least for the most mainstream interpretations. Superdeterministic, multiverse, and de Broglie-Bohm interpretations evade this.

Join the discussion on Substack!