Can we Trust Self-Reported Mystical Experiences?

Some heuristics for evaluating experience reports

View on SubstackThere’s been a lot of talk about the jhānas (meditative states of absorption) lately. Scott Alexander seems to have kicked it off by highlighting Nick Cammarata’s self-reported experiences, which were met with a good deal of skepticism.

How much can we trust Nick and other meditators to faithfully report their experiences? I spend a lot of my time reading about and trying to reproduce these experiences, and I’ve come up with a few heuristics for judging reports. I’d like to share them here.

Outline

A Hard Problem

Reading Minds

Deciding whether to trust a self-reported mystical experience is radically hard.

It’s impossible to verify someone’s state of mind directly—if you say you’re in pain, I just have to trust you. There are some neurological signals that correlate with particular subjective states, but for the most part we have to judge people by their words.

When many people report very similar experiences, we can have a little more confidence. Scott writes:

When people say they have migraines, this is mostly just self-reported introspection, but we still trust them. We trust them because lots of people say it, because they seem like trustworthy people, because it’s not so implausible that sometimes people get lots of pain in their head for weird reasons, and because (contra Johan) we don’t actually have a principled position of never believing self-reports.

But that still leaves us in the dark on any particular case. If someone tells me they suffer from migraines, I might distrust them due to a history of hypochondria or attention-seeking.

(Edit: some have pointed out this is actually not a great example—there are physiological correlates for migraines. But you get where we’re going here: good medicine/science can still take self-reports into consideration.)

To make things worse, if there are a large number of hypochondriacs and attention-seekers out there, they will skew our beliefs about what migraines feel like with false reports.

Ego Death is an Ego Boost

With migraines, the epistemological issue isn’t so bad that we need to take it seriously. With mysticism, it’s much harder, for two reasons.

First, these states are notoriously difficult to attain. People spend years in seclusion hoping to cultivate them, and even then there are no guarantees. This makes it hard to verify any claims that don’t involve drugs.

Second, and more importantly, there are huge social and psychological rewards for believing you’ve reached a special level of spiritual attainment. Enlightenment is the ultimate status symbol. There are an absurd number of Redditors out there doing AMAs about how enlightened they are.

That doesn’t mean these people are outright lying. I think many of them really do feel something, and genuinely believe it’s the thing. But more often than not they’re projecting a pre-formed narrative onto their experience.

I often feel this temptation personally. Maybe I read that I’m supposed to feel my “sense of self dissolve”, and then I feel some tingling and mild proprioceptive shifts. I’ll be inclined to describe this as my “self dissolving,” even though I wouldn’t have used those words without being primed for them.

Sam Harris describes a Swiss woman who declared herself “enlightened” to Dzogchen master Tulku Urgyen:

…he gave a short laugh and looked the woman over with renewed interest.

“How long has it been since you were last lost in thought?”

“I haven’t had any thoughts for over a week,” the woman replied.

Tulku Urgyen smiled. “A week?”

“Yes.”

“No thoughts?”

“No, my mind is completely still. It’s just pure consciousness.”

“That’s very interesting. Okay, so this is what is going to happen now: We are all going to wait for you to have your next thought. There’s no hurry. We are all very patient people. We are just going to sit here and wait. Please tell us when you notice a thought arise in your mind.

…After a few moments, a look of doubt appeared on our friend’s face.

“Okay…Wait a minute…Oh..That could have been a thought there…Okay…”

Over the next thirty seconds, we watched this woman’s enlightenment completely unravel. It became clear that she had merely been thinking about how expansive her experience of consciousness had become—how it was perfectly free of thought, immaculate, just like space—without noticing that she was thinking incessantly. She had been telling herself the story of her enlightenment—and she had been getting away with it because she happened to be an extraordinarily happy person for whom everything was going very well for the time being.

It’s very easy—and very tempting—to trick yourself here. It’s even easier (and more tempting) to trick others. Skepticism needs to be our default attitude when dealing with mystical states.

Heuristics

Here are a handful of heuristics I’ve found to be helpful when reading reports of mystical experience. They’re particularly good for evaluating potential teachers.

Silence

He who knows, does not speak. He who speaks, does not know.

—Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

The first heuristic is paradoxical: the first rule of enlightenment is you do not talk about enlightenment. There are a few reasons for this.

First, experiencers understand that talk is cheap. Anyone can make claims here, and it’s impossible to distinguish a true claim from a false one. So why waste words?

Second, words are ineffective. The most common word used to describe meditative states is “ineffable”. Trying to describe ego death to someone who has never felt it is like trying to describe green to a blind person.

Third, if you’re a teacher, you run the risk of polluting your student’s expectations. They can interpret your (inadequate) words to mean many different things, and be mislead. And it makes it easy for the student to counterfeit an experience by regurgitating the teacher’s words.

Of course, people do give reports about their experiences, and we can’t write them all off as fake just because they’re on Twitter. Everything is on Twitter.

Specific Sensations

The second thing to look for is reports of specific sensations: tingling in the hands, bursts of energy up and down the spine, proprioceptive changes, etc.

Teachers rely heavily on these sensations, since they serve as concrete landmarks on the path to particular meditative states. They also tend to come early on, making them easier to verify.

These sensations are mostly tactile or proprioceptive, but can also include visual and auditory sensations (I’ve never heard a report including a taste/smell sensation, but you never know).

An example: Robert Thurman tells of his first mystical experience with several tactile and proprioceptive descriptors:

I experienced a disorienting sensation that I can only describe as the feeling of a push-pressure on my tailbone suddenly dislodging itself…The change in sensation gave me a pronounced feeling of relief, a sense of release…A ripple of relaxation moved down my frame, and I felt buoyed by the released momentum.

Or Leigh Braniston on the first jhāna:

Pīti can manifest as rocking or swaying…It can manifest as heat and get very, very warm…Most often, it manifests as an upward rush of energy, often centered up the spine.

Novel Descriptions

Enlightenment is like everyday consciousness but two inches above the ground.

—D.T. Suzuki

It’s easy to counterfeit an experience by regurgitating someone else’s description, or by using simple analogies. Reports that use novel imagery to describe the experience are more trustworthy, especially if the description coheres with your own (possibly limited) experience.

Language is notoriously inadequate for describing exotic inner states. When describing non-specific sensations—e.g. emotions, or extreme proprioceptive distortions—teachers typically resort to poetic, metaphorical language. They’ll also speak in terms of paradox, like “thunderous silence” or “terrifying beauty”.

Anytime I attempt to describe an exotic mind state I’ve experienced, I’m disappointed by the result. I’ll describe it as euphoric, but that doesn’t capture the undertones of anxiety. Or I’ll describe it as terrifying, but that doesn’t capture the apocalyptic excitement. So mostly I just keep my mouth shut.

The best reports are from gifted writers like Michael Pollan and Aldous Huxley, and they spend paragraphs dancing around the experience. Here’s Pollan’s description of an ego-death experience while listening to Yo-Yo Ma play Bach (psychedelic-induced, but still instructive):

…”listen” doesn’t begin to describe what transpired between me and the vibrations of air set in motion by the four strings of that cello. Never before has a piece of music pierced me as deeply as this one did now. Though even to call it “music” is to diminish what now began to flow, which was nothing less than the stream of human consciousness, something in which one might glean the very meaning of life and, if you could bear it, read life’s last chapter.

…Four hours and four grams of magic mushroom into the journey, this is where I lost whatever ability I still had to distinguish subject from object, tell apart what remained of me and what was Bach’s music. Instead of Emerson’s transparent eyeball, egoless and one with all it beheld, I became a transparent ear, indistinguishable from the stream of sound that flooded my consciousness until there was nothing else in it, not even a dry tiny corner in which to plant an I and observe. Opened to the music, I became first the strings, could feel on my skin the exquisite friction of the horsehair rubbing over me, and then the breeze of sound flowing past as it crossed the lips of the instrument and went out to meet the world, beginning its lonely transit of the universe. Then I passed down into the resonant black well of space inside the cello, the vibrating envelope of air formed by the curves of its spruce roof and maple walls. The instrument’s wooden interior formed a mouth capable of unparalleled eloquence—indeed, of articulating everything a human could conceive. But the cello’s interior also formed a room to write in and a skull in which to think and I was now it, with no remainder.

So I became the cello and mourned with it for the twenty or so minutes it took for that piece to, well, change everything.

This is a beautiful description of what it’s like to listen to music during meditative absorption. It coheres with my own experience, but articulates it in ways I would not have dreamed of. This leaves me with little doubt that Pollan has felt some of the things I’ve felt (and possibly much more).

By contrast, when a report seems to regurgitate common platitudes or make simplistic analogies, it’s hard to trust. Granted, the experiencer might just be a bad writer.

Bivalence

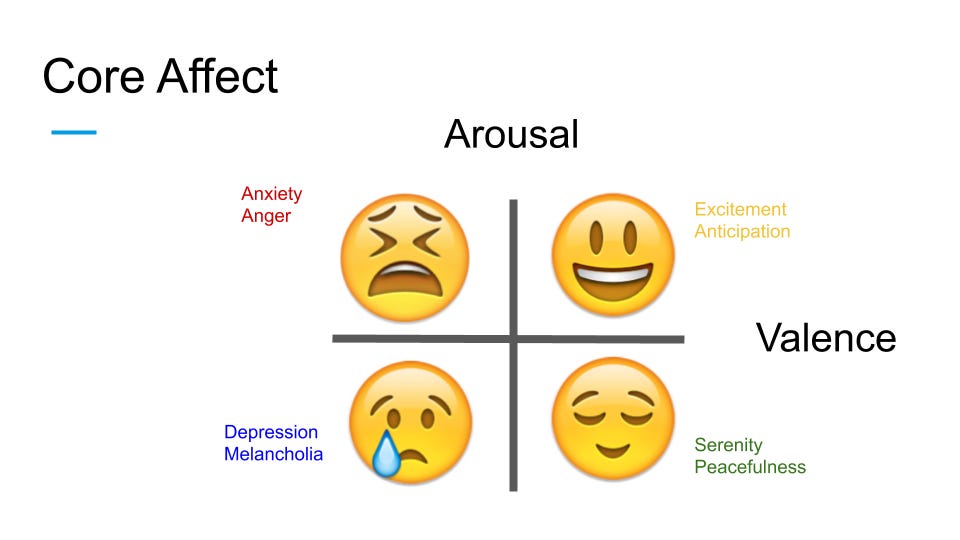

A working hypothesis of mine is that every positive-valence state is paired with a corresponding negative-valence state, and vice versa. This is certainly true for mundane emotional states.

Anyone who has managed to find their way repeatedly into an exotic mind state has likely explored the surrounding territory, and seen both its positive-valence and negative-valence manifestations. Someone trying to win your money, attention, or adulation (i.e. trying to sell you something) might neglect to mention the downside.

For a good example, here is Leigh Brasington describing the negative aspects of the first jhāna, which some describe as “extreme bliss”:

The pīti, being the physical release of pleasant, exhilarating energy, could be anywhere from mild to quite intense. It can be finger-in-the-electrical-socket intense; it can be so intense that it’s not even pleasurable…It may generate insomnia until it calms down…definitely an unpleasant condition.

There is also some disagreement over whether positive valence can be maintained permanently. A lot of traditions look for stable, neutral mind states, and emphasize the need for equanimity. So I’m somewhat skeptical of the sustained “mega bliss” states reported by some practitioners.

Subjectivity

One of the worst mistakes an experiencer can make is taking their personal experience as universal. I’m reminded of a charlatan who claimed he’d seen the thousand-petalled lotus, but counted and only found 999 petals.

Every good teacher understands that different people will need to take different paths to get to the same mind state. And that ultimately we are dealing with subjective content, which will manifest differently for different people.

Here’s The Cloud of Unknowing, a 14th century Catholic mediation guide:

It is important to realize that in the interior life we must never take our own experiences (or lack of them) as the norm for everyone else. He…may easily be deceived if he speaks, thinks, or judges other people on the basis of his own experience.

For a more concrete example, here’s Brasington again, this time on the fifth jhāna:

If you are a visual person, you will likely “see” the space. Sometimes it appears as off-white or light gray—there may or may not be a horizon line. Sometimes it appears as black…If you are not a visual person, you might not “see” the space, but somehow you will know it’s there.

For an extended discussion on the subjectivity of mystical experience, I highly suggest Robert Thurman’s introduction to the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Failure to recognize the subjectivity of an experience doesn’t invalidate the experience itself. But it does make me question the reporter’s maturity (and sometimes their mental health).

Skepticism In Practice

None of this should be taken as gospel. These heuristics are a reflection of my own experience, and “we must never take our own experiences (or lack of them) as the norm for everyone else.”

But the world of spirituality is rife with nonsense and outright fraud. There are plenty of people out there who will happily promise you “mega bliss” for the low price of $4200/month. And there are a lot of people paying that $4200 who will claim they’ve felt it—only to add strong qualifications after being deprogrammed (the documentary Holy Hell describes this experience well).

Given the ease of lying about mental states, and the strong social and monetary incentives to lie about them, it’s important to take a default attitude of skepticism towards self-reports. Even when many individual reports line up, we need to remain cautious due to the potential for self-deception, feedback loops, and mass delusion.

I hope it’s clear that I do believe in mystical mind states, and that meditation can lead us to them. But without proper skepticism, we’re likely to get lost.

Join the discussion on Substack!