Ayn Rand Will Kill Us All

Greed, Logic, and AI Doom in Atlas Shrugged

View on SubstackFirst, a confession: I read Atlas Shrugged in my early twenties, and fell in love. I’d just landed my first job out of college, and it was more prestigious and higher-paid than any job my classmates had gotten. I saw myself reflected in the book’s protagonists: uncommonly intelligent1, profoundly innovative2, and morally resolute3.

Rand offered me entrance to a world where I deserved this job and its fruits, a world where luck and privilege are myths constructed by the envious. A world where I was literally superior to other people.

Which is obviously bullshit.

Outline

First, I’ll give a brief overview of the bits Rand gets right in the Capitalism/Communism4 debate. Then we’ll have some fun picking apart her strawman.

Finally, we’ll dig into the more important point here: why her ideas are so alluring to people like 23-year-old me, and how a veneer of logic can mislead us.

A is not A

Rand uses logic, game theory, and thought experiments to demonstrate that pure Communism—”from each according to their ability, to each according to their need”—inevitably collapses. It disincentivizes productive behavior and encourages neediness, driving away the best and attracting the worst. And when there are no positive incentives, violence is the only way to make people productive.

When money ceases to become the means by which men deal with one another, then men become the tools of other men. Blood, whips and gun—or dollars. Take your choice—there is no other.

—Francisco d’Anconia in Atlas Shrugged

In fairness, for small, tightly-knit groups, where everyone knows everyone, the Communist system can work—there’s enough goodwill and social pressure to keep people honest. But at a civilizational scale, a few misanthropes are bound to cheat. And if you see your neighbor slacking, it becomes hard to stay motivated. Communism is a perpetual fight against the sinkhole of Nash equilibrium.

The power of Capitalism, on the other hand, comes from its hard-nosed acceptance of humanity at its worst. It sets up a system of incentives where people are expected to do no more than act in self-interest. Any altruism is anomalous, a happy rounding error.

In other words: Capitalism is pessimistic but stable, while Communism is optimistic but unstable.

You might think stability is worth the price, or that it’s simply inevitable—the unstable systems collapse, leaving only the stable systems. But there’s a tradeoff here. Stability isn’t everything—if it were, all our buildings would be pyramids.

The problem, as we’ll see below, is black-and-white thinking. While Rand’s thought experiments demonstrate that naive Communism (metaphorically, an inverted pyramid) is doomed to fail, she’s too quick to leap to the opposite conclusion: that Communism’s polar opposite must be the best possible system.

Contradiction

I could digress here with a bunch of empirical evidence that middle-of-the-road economies are superior to both hardline Capitalism and hardline Communism. I could cite statistics on inequality, growth, and happiness, or point to the success of mixed economies over the last century.

I could also point out that Rand is playing on easy mode—she gets to construct a fictional universe to support her claims. Sure enough, the book lacks any characters who are disabled or elderly; one homeless character tells us he lost everything when Communists took over his factory; another repeats the Randian slogan “Who is John Galt?”—most homeless people are Free Market Capitalists, right?

But fortunately I don't need to do all that. Rand undermines her own “greed is good”5 argument in two ways.

First, the main characters—heroic inventors and industrialists—aren’t driven by greed, but by the sheer love of seeing their creations come to life. This tracks with my own experience of highly innovative people.

One scene flashes back to the main characters as children. We learn that Francisco has independently discovered differential calculus at age 12, in the course of building a “complex system of pulleys” to help him jump off a rock into the Hudson.

In another scene, we see heroes Dagny and Hank riding her brand new train line built on his brand new patented steel, with overtly sexual excitement. Sure, Dagny tells the press she “hopes to make a ton of money” on the new line, but in truth she and Hank are just total geeks for trains. They squee over steel manufacturing and engine design.

Second, the main villains in Atlas Shrugged are all greedy profit-seeking bastards—mainly politicians and crony businessmen who use their power to leech the value created by the book’s heroes. Ironically, these are the same villains as in the Communist worldview: the fat cats who live off the hard work of others.

According to Rand, these leeches can only emerge in a society that extracts value from its citizens “at the point of a gun”—that is, in the form of taxation. What she fails to acknowledge is that Capitalism breeds non-productive elites.

There’s a level of wealth, measured in the low millions, after which you can live a decent life without working. You can put your money in a diversified portfolio of medium-risk, medium-reward assets like real estate and corporate bonds, and generate a ~5% return annually. With $1M down, that’s $50k/year, roughly what the median American earns6. All without lifting a finger.

Things get even more bizarre at higher levels of wealth. If you can afford to push your money towards high-risk, high-reward investments, you can expect to earn 8-12% each year. Even just parking your money in the S&P 500 has historically generated returns north of 8%7, and that's before you gain access to the sorts of vehicles that are reserved for sufficiently wealthy "accredited investors", like venture capital and hedge funds.

8% might not seem like a lot, but thanks to the miracle of compound interest, it means doubling your money every nine years. Start with $10M at age 30, and you’ve got $320M by age 75. All you have to do is log into your brokerage account and click a few buttons; then you can sit back and watch as your daily return exceeds what the average person makes in a lifetime8, all because the Fed lowered interest rates by 10 basis points.

The myth is that these ultra-wealthy people are making sophisticated decisions about how to “allocate capital”, making sure healthy companies get funded and letting unhealthy ones die on the vine. In truth, that work is done by salaried employees: financial advisors, hedge fund analysts, maybe even a family office. When the wealthy actively manage their own money (e.g. through angel investing), they tend to lose it.

Another myth is that these people have made their wealth though some combination of hard work and brilliance. But for every self-made billionaire out there, there are 2-3 multi-millionaire descendants. And as we’ve seen, it only takes a decade for a fortune split in two to regrow to its original size. Without a robust estate tax, extreme wealth is a value-eating hydra—every descendant of a billionaire can consume extravagantly without working.

To put a fine point on it: pure Capitalism is just as perverse as pure Communism.

Both-And

If Rand’s arguments are this flimsy, why is Atlas Shrugged so popular?

In the 1990s, a survey by the Library of Congress named Atlas Shrugged as the most influential book in the US, after the Bible.

Part of the appeal is that, much like Marx, Rand dresses up her Capitalist Manifesto in logic.

When I read Atlas Shrugged, I’d recently completed courses in symbolic logic and set theory, and was immediately drawn to chapter titles like “A is A” and “Either-Or”. Rand’s tone throughout the novel is that she’s only stating basic, commonsense facts, and that anyone who disagrees must be hopelessly confused or committed to a contradiction.

The basic syllogism of Atlas Shrugged is this: pure Communism is horribly bad; the opposite bad is good; therefore pure Communism’s opposite, pure Capitalism, must be amazing.

Good = -Bad

Capitalism = -Communism

Communism = Bad

=> -Communism = -Bad

=> Capitalism = Good

Q.E.D.Fortunately, I pursued my interest in the foundations of logic far enough to learn that no axiom is sacred. In particular, I’ve developed a strong distaste for The Law of the Excluded Middle9: the notion that either a proposition is true, or its negation is true, with no room in between.

The Law of the Excluded Middle seems like common sense, almost too obvious to mention. Wikipedia calls it a “fundamental axiomatic rule…upon which rational discourse itself is often considered to be based.” Surely any system of logic would collapse without it!

And yet there are reasonable criticisms and alternatives. For instance: any moderately powerful system of logic contains statements that are “unprovable”—neither true nor false given the system’s axioms. There are also logical systems and programming languages which allow statements to take on intermediate values between “true” and “false”, like probabilities or amplitudes. At the quantum scale, the universe itself appears to operate this way: the statement “a photon is in location X” often has no truth value.

Outside toy systems of logic, the Law of the Excluded Middle leads to black-and-white thinking, a cognitive pattern so common and problematic that it’s recognized as a logical fallacy. Sure enough, Rand (who titles one of her chapters “Either-Or” in direct reference to the Law of the Excluded Middle) falls right into this trap. And her readers often fall in with her.

Sticky Ideas

As we’ve discussed before, some ideas are radically sticky—they’re what Richard Dawkins might call a “successful meme”. Once you’ve adopted the idea and shifted into its worldview, it’s hard to extricate yourself.

A common example here is the fear of hell: the consequences of damnation are so extreme that even the slightest possibility demands attention. It can take decades to deprogram someone raised in a fire-and-brimstone cult; most never escape.

But for many of us—including myself—the most insidiously sticky ideas are dressed up in scientific or logical rigor. The language of reason creates an illusion of certainty.

Sometimes we can uncover this trickery through rational discourse—e.g. the sections above make a rational argument that Rand is wrong. But too often the logic serves as armor for a belief that carries emotional appeal. We might listen to a counterargument, but we won’t hear it.

The mistake is that…it’s not just a logical deduction, but, so to speak, a deduction that has turned into a feeling. Not all natures are the same; for many, a logical deduction sometimes turns into the strongest feeling, which takes over their whole being, and which it is very difficult to drive out or alter. To cure such a person, it’s necessary in that case to change the feeling itself, which can be done only by replacing it with another equally strong. That is always difficult, and in many cases, impossible.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Adolescent

Here’s Michael Polanyi quoting a repentant Marxist:

My party education had equipped my mind with such elaborate shock-absorbing buffers and elastic defences that everything seen and heard became automatically transformed to fit a preconceived pattern.

And the same for a former Freudian:

The system of theories which Freud has gradually developed is so consistent that when one is once entrenched in them it is difficult to make observations unbiased by his way of thinking.

Perversely, the more intricate and multifaceted the logic, the stickier its conclusion gets. A longer exposition gives the reader confidence that the argument has been thoroughly thought out, but gives the author more places to hide assumptions and loose definitions.

When we dress our beliefs up in rational argument, we ironically end up constructing an iron-clad fantasy world. We convince ourselves that we’re immune to emotional appeal, that we alone have the pragmatic sobriety needed to see the situation clearly. But often all we’ve done is add a protective layer of reason around something that feels true.

Modern Parallels

I don’t mean to pick on Rand or her acolytes. Well, maybe a little—but only because I’m a former member of their club.

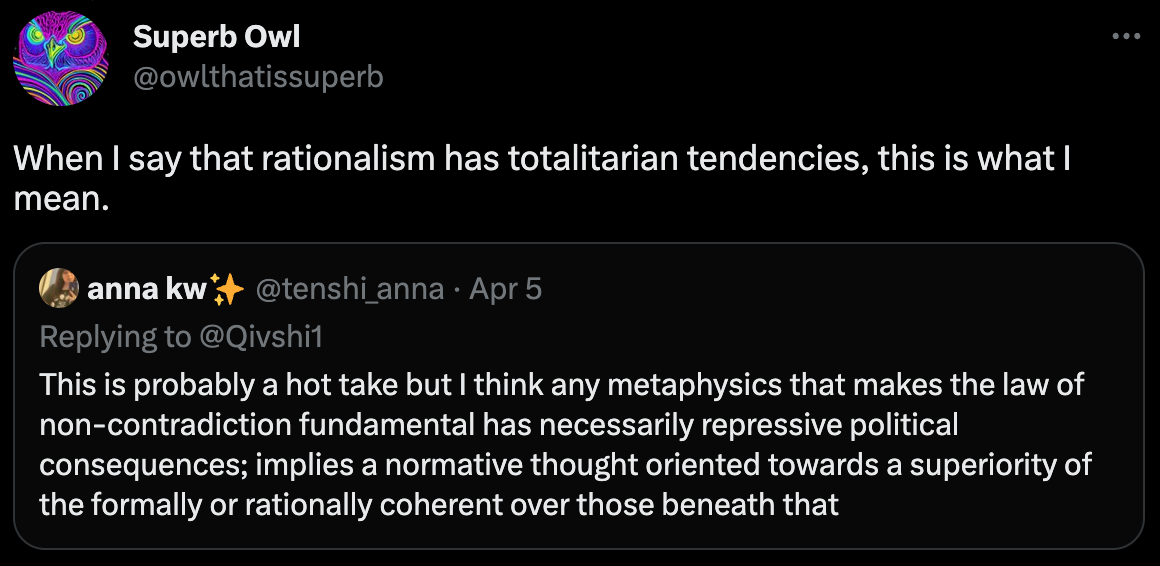

Fact is, the same dynamic plays out in a wide variety of contexts. Smart people become invested in an idea, often for emotional reasons, then they launder their beliefs through a veneer of rationality.

I see this happening in arguments supporting theories of racial intelligence. They have all the structure and flair of rigorous science—controlled studies, statistical analysis, etc—but their main appeal is emotional. Much like Rand, they grant the believer access to a world where privilege is completely deserved, a world where racial inequality is not injustice, but a structural feature of reality. Most importantly, believers get to see themselves as brave thinkers who have uncovered “forbidden knowledge”, as Sam Harris calls it.

(To be fair, the converse is also true—the counterarguments make the same flimsy appeals to science, statistics, and reason, despite clearly arguing from an emotional stance of “racism is bad”. But I’m more sympathetic to that emotion.)

AI Doom is a more contemporary example of emotion masquerading as reason. Just like with Rand, I think there are are some genuine insights here, but the loudest voices are so high on their own arguments that they’ve lost their minds.

Much like Rand’s 1000 page manifesto, the argument for AI Doom is spread out across dozens of massive Less Wrong posts. There’s no real canonical source; if you want to honestly judge the argument for yourself, you have to marinate in a rabbit hole of blog posts and YouTube videos until you feel terrified.

Again, there’s an emotional appeal which clouds our judgement: the fear of extinction (much like the fear of hell) is so extreme that even the slightest possibility demands attention. And like anything, the more attention we give it, the bigger it starts to seem.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean the opposite is true. People take the opposing stance for equally emotional reasons—they don’t want to think about apocalypse, or they have a naive faith in human ingenuity. My point isn’t that one side is stupid and the other is smart; my point is that the whole argument is obscured by emotion, to a level where rational debate is little more than noise.

It’s interesting to note the resonances between the AI Doom argument and Atlas Shrugged: Rand wants us to let the innovators innovate, with zero constraint. According to Yudkowski, that’s precisely the dynamic that’s leading us off a cliff at 1000 miles per hour.

So if you’ll allow me a moment to engage in the sort of black-and-white thinking that we all love, I’ll take Yudkowski’s side. The exponential growth of Capitalism is a cancer. If we don’t eradicate Randian Objectivism from our collective memory—if we allow this mythos of the heroic innovator to persist—humanity will be extinguished in a storm of AI-generated paperclips.

If we listen to her, Ayn Rand will kill us all.

Turns out, not so much

Turns out, not so much

Turns out, not so much

Rand doesn’t really attack Communism by name, but it’s pretty clearly set up as an antithesis to Capitalism (e.g. the scourge of “People’s States”). Rand’s target is really any form of taxation or regulation that might impede progress.

I should be clear that this not a direct quote from Rand, but it’s probably the most succinct summary of her philosophy. Some actual quotes:

Capitalism has been called a system of greed—yet it is the system that raised the standard of living of its poorest citizens to heights no collectivist system has ever begun to equal, and no tribal gang can conceive of.

If workers struggle for higher wages, this is hailed as "social gains", if businessmen struggle for higher profits, this is damned as "selfish greed".

Since time immemorial and pre-industrial, 'greed' has been the accusation hurled at the rich by the concrete-bound illiterates who were unable to conceive of the source of wealth or of the motivation of those who produce it.

This was corrected. See the comment from Tony for discussion.

Another user also points out that there are asterisks here related to volatility and risk, which I don’t think invalidate the point much—but maybe you need $2-3M if you really want to milk out $50k a year without worry.

2% (a not-uncommon daily swing in equity markets) of $100M would be $2M. The most optimistic estimate I found for median income globally is $9,733, which might generate half a million over a lifetime of work.

Really my beef is with the stronger Principle of Bivalence, but the phrase “Excluded Middle” has more poetic appeal. I conflate the two here, as well as the Law of Noncontradiction. There are important technical distinctions between all three, but for our purposes we can appeal to the common denominator: rigid, commonsense systems of logic are naive and impractical.

Join the discussion on Substack!